Doctor Simbo

Prosecutor: And who was Doctor Simbo?

The working title was Close Encounters Of The Murderous Kind and the first entry of the planned series was in that vein but, once encountered, I felt that he deserved the eponymous treatment, let me know how it fits...

I. Close Encounters

Prosecutor: And who was Doctor Simbo?

Witness: He was a Ghanaian.

I first met him in the court transcripts and, within minutes, he evoked the same mixture of horror and recognition that Mr Hyde must have surely raised to Doctor Jekyll. Although I suspected that the name Simbo was a pseudonym, I had no reason to doubt the witness's notion that he was a doctor, nor indeed that he was a Ghanaian. And this last, I suppose, was what first alarmed me, his countryman. His appearance was a mere footnote to an overlong trial, the fugitive glimpse of the man, revealed during a fishing expedition by a prosecutor who really should have stuck to the wealth of stronger material at hand. But I appreciated the strategic ambition of that servant of the International Criminal Court, immersed as she was in all that murky talk of warlords; for there he was outlined in those few furtive paragraphs. Really! What was he doing there in that lugubrious free-for-all? What was he doing there amongst that gruesome lot, knee deep in their ruthless bloodlust? How did he come to be embraced by them, the most notorious proponents of summary amputations, surrounded by the most hallucinatory child soldiers we have seen. Hell, those guys even put the Lord's Resistance Army to shame. I had to reassess things even as I remembered all their victims. But I held on to the witness's statement: his name was Doctor Simbo, and he was a Ghanaian.

There are many who think that God watches over Ghanaians, keeping us from the brink whenever full blown disaster beckons. By contrast our Nigerian brethren seem to laugh at brinks and disdain cliffs. We congratulate ourselves that somehow we've avoided the kind of mess that is fodder for cautionary tales about Africa. It's a kind of faint praise really: things could be worse, things could have been much worse. I dissent from this kind of talk even as I recognize its power, for I obsess rather with how much better things should have been, how much better things should be now, and indeed how much better things should be going forward. But well, that's the claim, your mileage might vary.

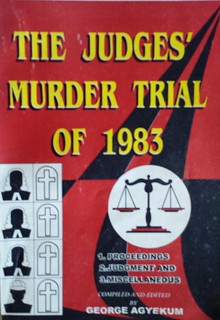

The canonical example is the providential rain that fell one June night in 1982 that prevented the bodies of the three judges and a retired army officer that Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings's junta had ordered murdered from being burnt beyond recognition. It was the dry, hot season and it hadn't rained in weeks. The death squad had set out, list in hand, supplied with curfew passes, operational permits and a Fiat jeep pickup obtained from the Head of State's wife's front yard (we have our Lady Macbeths too). The houses had been pointed out to them previously. They rounded up their prey from their homes and family, ostensibly for questioning (we were months into arbitrary military rule), or, more cruelly, to assist an ailing colleague. They drove their victims to the Bundase Military Range near Dawhenya and the Shai hills, sat them on concrete blocks, shot them, poured petrol on their corpses, and set them on fire.

Their disappearance was not supposed to be acknowledged. The country was rather meant to join the company of those with a community of 'disappeared'. The intent was terror, striking at the core of the Ghanaian establishment that was quietly opposing the "31st December revolution", a settling of scores for past slights, and, well, this was only meant to be a beginning. Breast-feeding mothers be damned, the revolution was moving too slowly. "Let the blood flow" was the refrain that was still echoing in the Castle, and Kojo Tsikata, Alolga Akata-Pore, and Jerry Rawlings were not afraid of other people's blood. A good culling, or more classically perhaps, a decimation was warranted.

The rain intervened and the bloodbath, the planned reign of Robespierran terror, was stillborn. A cattle herder came across the partially-burnt and maggot-infested bodies in the morning and the foul murders were discovered and investigated. Cold comfort as it is to the families of those slaughtered that day, the potential death toll of the planned campaign and, well, the course of Ghana's history was changed. Initially we were told that the murders were to be blamed on counter-revolutionary saboteurs who had "adopted the tactics of terrorists by the kidnapping and murder of innocent citizens in order to create an atmosphere of fear and panic among the population and to use this an an opportunity for further action". The contingency scripts had been readied and the complaisant Western media outlets played their part. Quickly however, the investigators unraveled things and it was found that the junta itself was responsible.

I shall skip over the inadequacies of the investigation, the performance of the regime's Attorney General, and the ensuing murder trial (held in one of those Public Tribunals that had been created to mete out rapid revolutionary justice). Those public servants did their best under the circumstances (after all, it's hard to point the finger at your boss or, indeed, the Head of State Security). I'll also gloss over the curious fact that the Leader of the Revolution felt the need to be Priest Confessor to his fallen comrade-in-arms, interrogating and tape-recording even as as the latter faced the firing squad a year later (presumably the need to secure an exoneration trumped all process and he obviously ducked out of the way just before the bullets started flying). Reading what we do have in the public record is disquieting; the casual tenor of the talk of these so-called radicals, their intrigues and their attitude towards blood, honor and betrayal. Personalized and vicious politics was our lot and clearly we had fallen on evil times. The revolution eats its own, I suppose, and I'd rather concentrate on its collateral damage.

The revulsion at the depravity of the PNDC reverberates to this day - amnesty provisions in the 1992 constitution notwithstanding. We had a glimpse of the abyss. We learned who was popping champagne on that rainy night. We learned in unchallenged court testimony about the dry run murders that had taken place earlier in the Volta Region. We learned about the various "special operations" that the Security Adviser to the PNDC and Head of Security had commissioned. We learned about the lists that had been drawn up in the previous months by these conspiratorial people who had conquered Ghana. We learned about the hundreds of people who were being coldly discussed at night while the rest of country was facing a curfew.

Closer to my home, the dinner table talk has occasionally drifted onto who else was on those lists of 'enemies of the revolution' targeted for liquidation in those heady days. People's positions in these lists are discussed stoically; visitors unaccustomed to such topics either shiver or laugh nervously as we talk. I should explain that my family history is replete with close calls with the wages of political violence in Ghana. From facing internal exile to being born in the shadow of death row, through an infancy of political prison and harassment, and a childhood of coup d'états, mere discussions of thugs and death squads are nothing new to me, or indeed to my family. We mask our heightened sensitivity to the wounds and wasted time with a kind of gallows humour. We always end by thanking the rain.

In the grand realm of things, the violence that military rule wrought in Ghana was not outlandish - albeit appalling, traumatic, and unnecessary of course. Our truth and reconciliation commission puts the death toll at 'only' a few thousand - open wounds on the scale of, say, a September 11th. Moreover the bulk of the killing and maiming took place spasmodically over the course of 20 years. Even at peak of the brutality (the frenzy of Rawlings coups), we can't really compare our lot to Chile, El Salvador or Argentina say, and, certainly, we got off lightly compared to other African imbroglios. Like many other African countries we had our lost decades after our bright post-independence starts. A couple of million Ghanaians went into exile - the bulk in the 1970s and 1980s, the rest embraced a culture of silence and quiet resistance. Simply put, we waited them out. Not for us civil war and fratricidal conflict. One of our great poets rather noted that we embraced the "mettle of invisibility", and developed our distinct philosophy of survival.

In any case, half of the country was born after democracy returned in 1992 and has no memory, or experience, of military junta rule. There have been hard times economically and otherwise since, but nothing compared to the deprivation of the 1980s. The larger economy has essentially grown every year since 1991 and, even when things have stalled, as presently, our political landscape has grown freer. There have been flashpoints, political violence and thuggery for sure, but we haven't had all out and widespread savagery. So yes, we had our close encounters, but Ghana didn't become Sri Lanka or Cambodia during the 80s, we didn't experience the scale of looting of our patrimony that Nigeria epitomizes, and we also didn't become the bloodied Kenya of early 2007 as repeatedly threatened during the 2008 elections. Such are the small mercies we live with.

I recounted the foregoing to set the stage for Doctor Simbo whose story I intend to unravel over the next few weeks, and I will raise the stakes here in light of what his very existence meant, because it seems that Ghana has been spared far worse: we're lucky that Ghana didn't become Liberia or Sierra Leone in upheaval. (Sidenote: I've previously discussed some of the larger forces that were arrayed in Ghana's recent political history, strange bedfellows ruled the roost in the 1980s. I've even worried about Ghanaian involvement and collateral damage in the 2005 London terrorist bombings).

Little did I know, however, that there were countrymen desperate enough to countenance the internecine civil war route. And let's put as plainly as can be: in the annals of iconic savagery, Charles Taylor's Liberian militias and Foday Sankoh's RUF of Sierra Leone are second to none, their stories are cautionary tales that should never be forgotten nor indeed emulated. So what was Doctor Simbo doing there with them? And as the prosecutor asked: who was Doctor Simbo? My belief in even the weakest kind of Ghanaian exceptionalism was shaken to the core as I read, and I still shiver when I think to the witness's answer: he was a Ghanaian.

See also

Some contemporaneous commentary:- But The Melody Lingers On from Talking Drums magazine, September 1983.

The question sadly remains unanswered: "When is an action of a member of the PNDC an individual matter and when is it a matter for the Council?" - Politicians, Politics and Policies in Ghana by Emmanuel Hansen.

Some of the clearest analysis of the time can be found in this book review from October 1984.

Soundtrack for this note

- Duke Ellington - Blood Count

I prefer the version recorded on his tribute to Billy Strayhorn with Johnny Hodges's delicate alto saxophone voicings, And his mother called him Bill. In memoriam. - Count Basie and Joe Williams - Too Close for Comfort

Count Basie swings, Joe Williams sings. Say no more.

Next in Part II: To Make the Road Fearful

In which we read about dark matters at the Special Court

See also: Truth and Reconciliation

File under: Ghana, culture, history, violence, blood, murder, coup, memory, politics, Sierra Leone, Liberia, war, observation, rogues, perception, Africa, The Rough Beast, Things Fall Apart