Prosecutor: Mr Witness, what did Reflection tell you about who shot Superman?

The transcripts of the Special Court for Sierra Leone, commonly called the Charles Taylor Trial, were a fascinating and disturbing glimpse into the conduct of a very dirty war. Nihilism was the trademark of most of the civil war's protagonists. The trial records feature not just garden-variety graft and basic criminality (the 'crime' part of war crimes), but mostly hallucinatory bloodlust and premeditated savagery (indiscriminate killings, routinized rape, summary amputations, forced drugs, cannibalism, etc.). War is hell; civil wars are hell; the descent of Liberia and Sierra Leone was an uncommon hell.

Still if you read the transcripts as I did in real time through the daily updates, you would have been confronted with a grand and unique body of literature, a mix of Kafka, Beckett, and plain Gothic horror presented in bureaucratic form. Truly, everything is in there.

For most observers, it was the child soldier narratives that were the most upsetting - overwhelming testaments to innocence lost and unconscionable cynicism, if not evil. For me, it was the observations of daily life during the wider Dante-esque free-for-all that resonated most. Additionally, there was a wealth of stories and conspiratorial detail to attract those afflicted with the journalistic impulse.

The setting was legal, with built-in confrontation and dramatic tension: Defense versus Prosecution moderated by The Court. There was the examination of Witnesses and Victims while Defendants looked on defiantly, denying everything, all of this shaped by the stylized conventions and terms of art of international law. The chaotic events described were mostly awful and occurred episodically over fourteen years, with protagonists from over a dozen countries, and affected millions of people; it was an international disaster through and through.

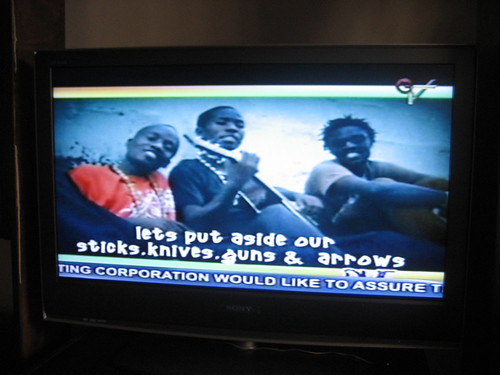

There was poverty and illiteracy on display - those already-poor countries became poorer still - and, indeed, could no longer even be called 'developing', during those wartime years. The language barriers were many, often obscuring comprehension during the trial - the creole and pidgin, and the many local languages of Liberia, Sierra Leone (Krio, Mende etc), Guinea and Cote d'Ivoire contending with the English, French and Dutch of The Hague to create a legal Babel of interpretation. The heavy accents essentially leap off the transcript pages. There were heaps of military jargon to further confuse things - for, although unconventionally fought, this was a bloody military war. And there would be smidgens of pop culture references, the warlords and their recruits (or rather prey) were young and enamored with football, reggae, hip hop and action movies (Stallone and Schwarzenegger would turn out to be big influences).

There were also fatally compromised actors in this drama. Many witnesses and defendants had considerable blood on their hands, a sizable number would often be lying through their teeth or, at best, furiously seeking to diminish their responsibility. And worse, many potentially valuable witnesses had come to bloody ends. Oftentimes the only remaining witnesses of crucial events would be lower level protagonists, say the drivers who drove the warlords to their nefarious meetings, or the radio operators who would arrange communications. Witnesses were often still traumatized about their experiences.

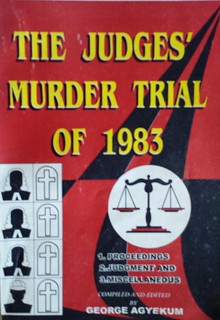

The concept itself of a Special Court and its legitimacy kept being brought up. Why was the trial focusing on events in Sierra Leone? What about all the atrocities in next door Liberia? Why confine prosecution to those "who bear the greatest responsibility" while allowing many murderers impunity? What about the truth and reconciliation committees that had been set up in those countries? What about the motley cast of foreigners involved, from Ukrainian and South African mercenaries, ex-CIA agents, through Al Qaeda types seeking blood diamonds from Lebanese and Belgian jewelers, Russian arms dealers, to meddling rogues and financiers like Blaise Campaoré and He of the Little Green Book, Colonel Gaddafi? There was enough culpability to go around. Despite all these difficulties, the lawyers had to tease out a grand narrative among the mountains of evidence, demonstrate a chain of custody, and establish clear findings of fact among the details. A challenging mess in short.

So. The Charles Taylor trial wasn't easy to digest but it had legal, journalistic and historical merit, not to mention an unexpected literary benefit. And it is this last aspect that transfixed me and kept me reading rather than grieving and despairing of humanity. It turns out that there's a certain poetry in these mundane transcripts, a kind of found art in the minutiae of these annals of cruelty. Where else would you find a more perfect sentence?

Prosecutor: Mr Witness, what did Reflection tell you about who shot Superman?

No fiction could equal this notion of Law and Order meeting The Last Philosophers in a comic book trial. Frankly I was hooked; I can't praise that sentence highly enough. Everything about it compels you to read or listen on. The text, the sub-text, the über-text, the text qua text! The formality of address is merely the beginning (Mr Witness). The testimony sought by the authority figure, The Prosecutor, is the second hand memories of The Witness about what someone named Reflection (Reflection!) confessed about the implied assault on (or death of) someone named Superman. Who is this person named Reflection? What was his relation to Superman? Why, to start with, does the prosecutor care about Superman? And, pray tell, did Superman die of the attack?

II. Conflict Readings

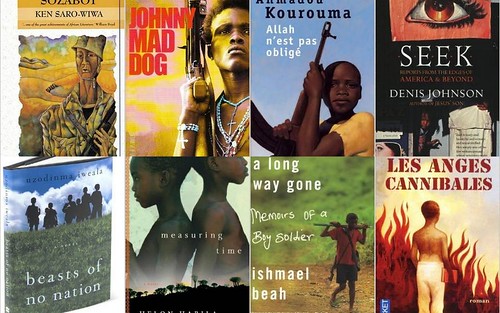

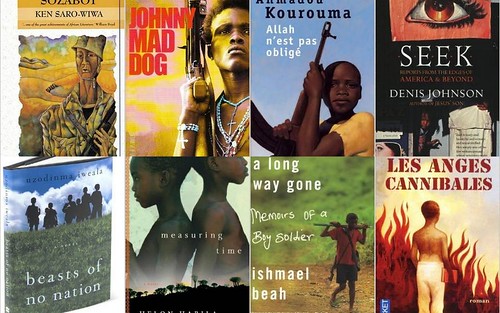

Some of our best writers have tackled the war, warlord, and child soldier narratives in African literature. The pinnacle of the genre of course is Ken Saro Wiwa's Sozaboy which deals with the Biafra conflict. There are also great works that focus specifically on the Liberia and Sierra Leonean imbroglio. Ahmadou Kourouma's masterpiece Allah n'est pas obligé is the best of the contemporary novels, a stunning achievement full of coiled menace and casual cruelty. Denis Johnson's reporting in Seek is hallucinatory; in particular, the reporting on Prince Johnson's torture and execution of the erstwhile Master Sergent, and then President, Samuel Doe, and the piece on Charles Taylor's Small Boy Units are unmatched in their immediacy (that phrase, Small Boy Units, being another grotesque, yet inspired, coinage). He sought out extremes and was unmanned by what he found. Emmanuel Dongala's Johnny Chien Méchant is simply scary - there's a fine English translation, Johnny Mad Dog. Helon Habila's Measuring Time treats the theme in a measured manner (it is a mere subplot of his grand novel) while Iweala's Beasts of no nation revels in surface style and linguistic gymnastics. Jean-Claude Derey's Les Anges Cannibales is a beastly mix of journalism turned novel and Léonora Miano's Les aubes écarlates stands out in its depiction of the dark episodes. Dealing with the militias in Congo-Brazzaville, Alain Mabanckou opted for restraint in Les Petits-Fils Nègres de Vercingétorix. Ishmael Beah's memoir, A Long Way Gone, by necessity of the form, can't take as much novelistic license, hence it is a more sober, if still harrowing, affair.

The unbearable reality these works address speaks for itself; the attending book covers merely highlight the distressing story. Journalists are typically the first to write about such things - although, often, their writings, being in the service of 'news', aim for the dispassionate rather than the urgent. When the writers have turned to fiction, the worlds they created were uniformly haunting; when they have drawn on their experiences, the reader yearns to escape their suffocating worlds. And it is this unreal reality they confront that we read at length in these trial transcripts of the Special Court. In contrast, we dare not turn away.

III. Naming Conventions

Let's start with the names, a mixture of military directness, macabre grimness and sheer horror. One can only find death and desolation in Operation No Living Thing or Operation Spare No Soul. And consider the cynical precision of Operation Stop Elections which introduced, and institutionalized, the alarming spectacle of random amputations as shock and awe. But what of Operation No Monkey, or the obvious invitation to marauding looting embodied in Operation Pay Yourself?

And what about the names of the wicked? Consider a few of the huhudious nicknames and noms de guerre: Jungle, Black Jesus, Savage, Crazy, Red Goat, Rocky, Rambo (there were many Rambos in the conflict - the one that that first caught my attention was the fearsome RUF Rambo), Zigzag Marzah, General 50, General 245, Five Five, General Dry Pepper (not to be confused with Dried Pepper), Captain Blood, Leather Boot, Gullit (lots of football nicknames as it turns out), Dawn-Dawn, Waco-Waco (there's joy in repetition), Butterfly, KGB, Zino, Black Diamond, the notorious Adama Cut Hand, The Devil, The Killer, Scare the Baby, Monkey Brown and groups such as the "Black Gaddafa", the Black Guards and the West Side Boys. And yes of course the aforementioned Reflection and Superman. To think that General Butt Naked didn't even figure in the trial (his murdering ways were confined to Liberia).

The mere names of the characters and the setting would be enough to summon a play by way of Ionesco. They need not be doing anything out of the ordinary to garner attention (imagine Scare the Baby discussing with Butterfly where to take Superman and Red Goat for dinner) let alone when those now questioning them are constrained with legalese ("my learned colleague", "I submit to you", further and better particulars etc). Adding the very surreal subject matter of this raging civil war serves to surface all the incongruity of a heightened theater of the absurd. Naming alone can drive the narrative.

A poignant counterpoint to these names of awful men and women is to consider their victims. It is truly sobering to read the listings of victims painstakingly compiled by the commissions and courts.

A._ (Female) age 13 - 1991 in Pujehun - Assaulted and raped.

F._ (Male) - 1998 in Bombali - Forcibly conscripted.

F._ (Female) age 12 - 1999 in Western Area - Abducted and detained. Raped.

G._ (Female) - 1995 in Moyamba - Forced to labour and sexually enslaved. Assaulted.

F.A (Female) age 10 - 1995 in Kono - Sexually enslaved. Tortured.

F.A (Female) age 16 - Forced to labour. Assaulted, tortured and raped.

A.B (Female) age 57 - 1997 in Port Loko - Displaced, extorted and property looted. Forced to labour. Assaulted and raped.

Charles, Bockarie (Male) age 53 - Displaced. Limb amputated.

Charles, Eyaja (Male) - 1998 in Kaiyamba, Moyamba - Tortured. Killed.

[ snip... lengthy and distressing listings of victims ]

The undeniable villain is Mosquito, Sam Bockarie, a man who wrecked bloody havoc and inspired so much fear for so long. He is cited as "a Battlefield Commander of lethal prowess and a deviant of unknown quantity... [who] committed human rights abuses with total abandon". Even more than the RUF's leader Foday Sankoh, and the ostensible target of the trial, Charles Taylor, his specter haunted the proceedings. Like the mosquitoes he was named after, he was not afraid of blood and indeed sought it out and seemed to relish vicious warfare and unrestrained cruelty. Sidenote: Bockarie suffered a very convenient death once it became clear that his ultimate boss, Charles Taylor, would be facing legal troubles.

Prosecutor: Just pause, Mr Witness. First you talk - once you spoke about the Master, that Master came. Who did you refer to when you said Master?

Witness: Sam Bockarie. I had said it once or twice here in this Court that we used to call Sam Bockarie Master, so any time I use Master I will be referring to Sam Bockarie. Then Father, we used to call Charles Taylor the Father. So at times - I am still used to calling him that way, that's why.

A lot of effort is spent on identity issues, naming is a fluid thing and prosecutors always have to double check what names are being used and when.

Witness: Later on, some of my friends called me Uprising.

The names are what witnesses hold on to in order to make sense of things.

Witness: Well, yes, like I recall CO Big Darling, one who was called Big Darling. And there was another called CO Nyamator and there was another with a nickname called CO After the War. So those were the kind of names they had. There was also another called Rebel Baby, CO Rebel Baby.

The Liberians were often the first to resort to nicknames for whatever reason.

Witness: Well, CO Lion was a Liberian vanguard and they were the ones who came to help train us in Sierra Leone to fight the war.

Context is everything.

Prosecutor:So, Mr Witness, just so we're clear, who were you with at that time?

Witness: I was with RUF Rambo at that time to attack Hastings and Jui.

Prosecutor: What other commanders were with RUF Rambo?

Witness: Rambo Red Goat, Crazy and others

Suffice to say that this parade of absurd names often diverts attention from some of the more consequential actors (such as Eddie Kaneh, Mike Lamin, Issa Sesay or Ibrahim Bah) and colors our perception of the acts that took place. And yes, for the record, Reflection was a radio operator for Benjamin Yeaten, Charles Taylor's right hand man. And Dennis Mingo (alias Superman) was a bad man: 'one of the foremost perpetrators of abduction-related crimes against children, including forced recruitment and forced drugging'.

IV. To Make the Road Fearful

The word "fearful" has a heavy burden in the history of the conflicts in Liberia and Sierra Leone. It was the adjective of choice for Charles Taylor and his acolytes for describing a crucial element of their wartime strategy. It is read entirely too often in the transcripts, a mournful thread running through the narratives that emerge. It is always uttered as an explicit invitation to murder and terrorism - with civilians as the frequent targets.

Taylor told one group of RUF soldiers, the "Black Gaddafa", that their mission was to "sabotage the movement of the enemy in Sierra Leone" by setting up ambushes and making areas 'fearful'. The witness said that Taylor and Sankoh ordered the troops to attack SLA and ULIMO forces, as well as capture civilians.

These injunctions would be taken to heart and the accounts of the subsequent misdeeds are often rendered in the most matter-of-fact terms.

Prosecutor: Was this attack only by the RUF or there were others involved?

Witness: the AFRC guys were involved

Prosecutor: Like who?

Witness: Gullit, Bazzy, Hon. Adams, Savage and other commanders

Prosecutor: Who were they all taking orders from?

Witness: Superman

Prosecutor: What happened during the attack?

Witness: We attacked Kono and we took over the town. We started looting and some of the commanders captured girls and made them their wives while some of us were burning houses

Prosecutor: Do you recall how many houses were burnt?

Witness: No I can't remember the figure

Prosecutor: Was there any particular reason you will select a house to burn?

Witness: Yes, one of the reasons was because there specific houses where Kamajors were based and some people pointed at house where people were supporting Kamajors

Prosecutor: Do you know if there were people inside the houses that were burnt?

Witness: Yes. When we set the houses on fire, we will hear the people inside screaming and when the house is burnt, we will see their skulls and bones.

And so with clinical precision, we get to the heart of the matter: blood and sin. Also note the hand of Superman.

Prosecutor: Did you take part in the Bumpeh attack?

Witness: Yes

Prosecutor: Were there opposing forces in Bumpeh when you got there?

Witness: No other forces were there so we attacked the civilians

Prosecutor: So what was done to the civilians there?

Witness: We asked them to leave the town. Some of them resisted, so we opened fire on them, we decapitated some and put their heads on the checkpoint.

Prosecutor: Why would you put the heads on the checkpoint?

Witness: To make the road fearful.

Prosecutor: Why would the RUF attack civilians in Motema and Bumpeh?

Witness: Because ECOMOG were advancing and we wanted to make the place fearful.

Prosecutor: Did RUF have any philosophy about treatment of civilians?

Witness: Well when civilians were based in the communities, they will take information in and out and so if we wanted to base there, we will get the civilians out of the town.

Prosecutor: Did you have any sense in the RUF about civilians?

Witness: We used to say civilians did not have blood

Prosecutor: What did you mean?

Witness: They were not as important as we were

Prosecutor: Did you see any difference in the way the AFRC treated civilians?

Witness: I did not see any great difference except the time we divided along the Freetown highway. We treated civilians in the same way

Prosecutor: Who led the attack on Tombodu?

Witness: Savage

Prosecutor: Do you know what happened during that attack?

Witness: Yes. Savage went there and did mass killings. They had a big valley there where he placed all the civilians. Superman and I went to Tombodu. Savage went and showed us the valley and Superman did not take any action.

Prosecutor: Can you describe the valley?

Witness: It was an old diamond pit.

Prosecutor: When your friends came back with girls from Motema, can you say the ages of the girls they came with?

Witness: Some were 14, some 20 etc. Some of them were in Koidu town with us and some at the Combat Camp. We even had one Michaela who was very small, about 14, who was with one of my friends.

Sexual abuse was pervasive:

Prosecutor: I need to go back to the attack on Makeni, what if anything happened to civilians there?

Witness: Most of the civilians, everybody got married. Whoever saw a woman will take her, some people looted.

Prosecutor: What do you mean by everyone got married?

Witness: We captured girls and made them our wives, we captured SBUs (Small Boy Units), gave them guns and got some civilians to work at our houses.

Prosecutor: What do you mean when you say they made them their wives?

Witness: They took them home, they slept with them

Prosecutor: What do you mean they sleep with them?

Prosecutor: We are all matured people here, so I can't go beyond that, but when you say you have sex with someone

Prosecutor: Who had sex with who?

Witness: The RUF had sex with the girls

Prosecutor: Was anything taken from Makeni?

Witness: At the first instance yes. The first two weeks, people looted and later Issa said he was Temne and those were his people, so he started killing people who looted.

Prosecutor: I think this will be a convenient point to stop.

I second the prosecutor's call to stop, if only briefly, because in reading we can only sink into despair when you consider some of the more infamous cases such as Adama Cut Hand, a girl "in charge of the small boys group that was known as Cut Hand Group" who wore a necklace of human hands and carried decapitated heads of village chiefs. A vision that wouldn't be out of place in Joseph Conrad's opus.

V. Not A Civilian Thing

Charles Taylor and Foday Sankoh had very clear ideas about what making places fearful entailed. It is important to remember that much of this infrastructure of terror was planned, and that many of the participants were mere instruments of their will.

Witness: We had a message that was from Foday Sankoh through CO Mohamed for all the stations which were at the front line to go and run Operation Stop Elections, to go into those towns where the elections were to be conducted and to cause panic there so that the people will not conduct the elections.

Prosecutor: What do you mean by to go cause panic there?

Witness: To go and shoot in the places so the people will be afraid; they will run away and the elections will not be actualized.

Prosecutor: Do you know where Sankoh was when he issued this instruction?

Witness: he was in Ivory Coast.

The testimony from compromised characters was always revealing in how they sought to downplay their own roles amidst the mayhem that surrounded them. The case of a close collaborator like Moses Blah, who had been there at the start and would become Charles Taylor's Vice President, is an interesting case in point. From his testimony, it would appear that matters of blood never reached him despite his proximity: he was merely political and had clean hands. Sadly prosecutors didn't question him about his motivations, these lawyers kept to their brief to prove the their limited case against his boss and didn't explore the historical or novelistic context. One has to read between the lines for psychological insight. On the other hand, Blah was prepared to spill the beans about others, or rather talk about the bread and butter of wartime atrocities:

[Moses] Blah recounted a few occasions when punishments were carried out against soldiers, but said only Taylor had the authority to order punishments. Blah was not allowed to investigate members of Taylor's special forces. Blah testified about complaints that the commander of the Executive Mansion Guard abused civilians at checkpoints. Blah further testified that he had seen the head of the Marine Unit eating roasted human hands. In addition, Blah said he heard of an incident where the head of the Marine Unit ate the intestines of a farmer cooked together with the man's cassava harvest. Blah said he was reluctant to complain to Taylor about these incidents because they would be considered an attack on the Executive Mansion Guard unit. Blah recalled Yeaten's involvement in atrocities, and stated that Yeaten never faced punishment.

According to Blah, in 1991 Sankoh complained to him that the NPFL soldiers were committing atrocities in Sierra Leone, including raping women, killing civilians, and looting. According to Blah, Sankoh discussed this problem with Taylor. After this meeting, Taylor complained to Blah about Sankoh and said:

"When you talk about a guerrilla war there's destruction and this is the type of thing - and this type of thing must happen if you are fighting a war. You are not eating bread and butter, you are fighting."

- Taylor's Former Vice-president Describes Training, Arms Deliveries and Atrocities, Claims Cannibalism was Required to Join Taylor's Presidential Guard

The bread and butter, as it were, of this war was making the road fearful, causing panic, and destabilizing people and places.

Prosecutor: What was this Operation No Monkey?

Witness: I was there when Benjamin Yeaten instructed Zigzag Marzah and other fighters to go to Belle Forest and destabilize all the civilians that were in the forest and anybody who refused should be killed and no monkey should even stand in front of them. That was why they named the operation Operation No Monkey. No monkey can stay in that forest. Everybody should move from that forest to come to the safer area, because the LURD fighters were trying to get into Belle Forest to come to Bomi Hills and attack Monrovia and indeed they used the route. Zigzag Marzah went there and did the operation in Belle Forest.

Others would express the same sentiment, although less quotably than Charles Taylor.

"I want the whole world and the Sierra Leone people to know that there is no war without atrocities" - the RUF's Francis Momoh Musah in a statement to the TRC on 2 May 2003

Or consider Gullit and Five Five during a meeting where the infamous amputation strategy was formulated, cynically, and out of frustration.

"When we started cutting hands, hardly a day BBC would not talk about us"

"For any war there must be an atrocity for the outside world to know there is something wrong in the place"

Some would say that these were post-hoc rationalizations for unrestrained savagery, and this is explored at length in well researched appendices in the truth commissions and in the trial documents: Amputations in the Sierra Leone Conflict.

There was little difference between Operation No Monkey and Operation Spare no Soul, these were all merciless affairs.

Witness: Well, I can recall at that time when they said Abacha had died, Sani Abacha. So it was during that time - I can recall that operation because at that time people were happy, the RUF soldiers were, the commanders, everybody was happy at that time.

Prosecutor: And do you recall exactly what happened during that period?

Witness: Well, it was that time - because that time when Abacha died was the time that that mission was arranged, because the Spare No Soul mission, Sam Bockarie said because Abacha had died and he was one of the big men for ECOMOG and that he was dead the soldiers would be weakened, everybody would be discouraged, so if they undertook any operation at that time they would be able to chase the ECOMOG out and they would be able to regain their positions because they were sad at that time and that would weaken them. That was why the mission was called Operation Spare No Soul and they were not to capture soldiers - they were not to capture ECOMOG soldiers and take them to him in Buedu. Spare No Soul meant that anybody who saw any of them, they should kill those soldiers. Any soldier they saw was to be killed. They were not to take any soldier to him in Buedu.

Prosecutor: And do you recall what happened during the course of this operation?

Witness: Yes, Komba Gbundema reported that they killed many civilians and ECOMOG soldiers too during this operation.

Prosecutor: When you say Alice Pyne told you this, how did she tell you?

Witness: Well, she came on and said they went on a mission and said that was how things happened, that they killed many civilians and they said - and she said anybody who saw them, that person was a dead person. And anybody they saw too, that person was a dead person.

If - Komba Gbundema's group, that is the RUF fighters, if they spared any - if they wanted to for example spare the civilian, that civilian's hand would be amputated. That would be the only way they would spare that civilian.

The horrible acts had a gruesome soundtrack

Witness: What I listened to I heard them saying, "People were daring. Man den get mind o way den wan kot pipul den an, den day say, 'Pull yu han pan di war. Pull yu foot pan di war'."

Prosecutor: When you say, "Pull yu han pan di war. Pull yu foot pan di war", do you know what that translates to in English?

Witness: Well I don't know if you want me to speak English directly, but what I understood by that as I said yesterday because the people whose hands were amputated were civilians, it was the RUF fighters who amputated civilians' hands and their feet and whenever they wanted to do this action that was what they told the civilians, the expression I just said in Krio, which meant that they were not to be involved in the war. They were not to have anything to do with the war. It was not the business of a civilian...

Judge Doherty: Yes, please. Mr Interpreter, please interpret those words which the witness has used.

The Interpreter "Pull yu han pan di war", your Honours, is translated "Take your hand off the war". "Pull yu foot pan di war" is translated "Take your foot off the war".

Such behavior is the signal and iconic legacy of Charles Taylor and Foday Sankoh.

Witness: Well, from what I understood, the Kamajors, like they called them, they were the Civil Defense Forces. I did not know that they had gone to any particular training base to be trained as combatants, or as soldiers. So we took them to be civilians who had guns, they had cutlasses, fighting against the RUF. Because they were calling them civilians, they were telling them that the civilians should take their hands off the war and to take their foot off the war, it was not a civilian thing.

Prosecutor: You said the RUF was using this expression. Who were they using it to?

Witness: Any of those civilians whom they captured when they were amputating his hand or foot.

But let us catch up with Superman a few months after the so-called Fitti-Fatta mission failed

Prosecutor: And exactly what was Superman instructed to do?

Witness: Well, Sam Bockarie told Superman that he should set one or two examples on civilians so that will instill fear in the other civilians and they will not be leaking information to the ECOMOG soldiers.

Prosecutor: How was Superman supposed to set examples - an example on civilians?

Witness: Well, he was to kill either one or two or to amputate some of their hands and to tell them to take their hands off the war...

Prosecutor: Do you know whether these instructions were carried out by Superman?

Witness: Yes, after two or three days I heard it over the SLBS radio that around the Kono axis rebels were cutting off civilians' hands and they were killing civilians.

Prosecutor: Is that all that you learnt about what happened?

Witness: After that, I enquired in the station, I went there, and it was not long after that that Sam Bockarie went there and he called Komba Gbundema to be sure that was what had occurred in the place. And Sam Bockarie told Komba Gbundema that that was enough, he said because as long as the whole world had heard about the killings and the amputations let that be enough, let it stop there.

Sometimes "fearful" is rendered as "fearsome", but the result is always the same:

Witness: ...before Issa left he said we were guerrillas and anywhere a guerrilla was you should make the area fearsome. In the RUF when we talk about making the area fearsome it is a word that carries different meanings. It means we should burn down houses, destroy other properties, killing and construct road blockades and destroy bridges. That would help in making the area fearsome. That was the instruction he gave.

In many respects the evidence against Charles Taylor was overwhelming, but his attorneys would argue that it was always second hand hearsay - after all people like Mosquito were dead and could not be cross-examined. Still, the extent of his ambition and hunger for power are brought to light in all the testimony.

Prosecutor: Did Sam Bockarie indicate to you in his discussions with Mr Taylor if there was any discussion about how the attack should be carried out in order to free Sankoh?

Witness: Yes, he said they discussed it. After he had shown those places to him they discussed that we should run that mission to ensure that we free Foday Sankoh and others and on the operation we should ensure that the ammunition is not wasted. We should make the operation fearful than all the other operations that we had undertaken because we want to make sure that we take Freetown and hold on to power.

VI. No Longer Human Beings

The pathology was widespread and it was all a few could do to simply bear witness:

Prosecutor: Who was Zigzag Marzah?

Witness: He too was a fighter in Liberia under Charles Taylor's government.

Prosecutor: How did you know that he was a fighter in Liberia under Charles Taylor's government?

Witness: Well I used to hear his name, but I never knew him. That was the first day I knew him.

Prosecutor: When you say you used to hear his name, what did you hear about his name?

Witness: Well, I used to hear people saying that he ate human beings, that he did not - he was not hesitant, he would kill human beings and he would eat human beings, and from that time I kept that name at the back of my mind. So when I heard that he was to come and indeed I saw him, I asked - I said, "Where is the man?", and he was pointed out to me and I looked at him, I stared at him, to know what sort of human being he was to be doing things like those. So, that was how I knew him.

Betrayals were commonplace and it turns out that Superman, a man who made his wartime reputation for abducting youngsters and training them to be Small Boy Units was killed by those he thought were friends.

Prosecutor: Mr Witness, what did Reflection tell you about who shot Superman?

The answer is that joint criminal enterprises are often unstable affairs.

In 2002 when the war intensified in Liberia, 2002 to 2003, when I used to go and fight and come back and sit down with him, he used to tell me, "Son, you are really trying for us, but we regret the death of your boss. People misled us to kill Superman." He told me that people told them that they used to see Superman at the American embassy. That was why they killed him, but he regretted. I had nothing to say. I just sat down and smiled. Yes, Benjamin Yeaten himself told me that he regretted why he killed Superman

One of the participants in Superman's death was the aforementioned Zigzag Marzah, head of Charles Taylor's accurately named Death Squad, and his cross-examination is hair-raising. That he is still walking around as a free man is one of the great injustices of the world. The headlines and summaries (e.g. Zigzag Marzah Says Taylor Ordered Cannibalism; Defense Works to Discredit his Testimony) simply do not do justice to the harrowing depths of the actual text. It should be read in full:

Defense: So you're talking about when the NPFL entered Liberia. Are you saying that at that stage Charles Taylor ordered you to eat Krahns?

Witness (Zigzag Marzah): I told you yes, yes. Any activity against which you did not take action was appreciated by him. What Doe did by taking our own people, not just Doe, Charles Julu, he himself went as far as eating some of the Nimbalian children from school campuses. When he kills them they would butcher them in the street. Like AK Pa [phon], he did that there so many times.

Defense: Now according to you at the time that the NPFL entered Liberia you were under the command of Prince Johnson who didn't allow this kind of thing. So help me please, who was it who told you to eat Krahns?

Zigzag Marzah: Thank you very much. Prince Johnson did not go far enough in the war. We were in Tiaplay when Charles Taylor wanted - his Specials Forces wanted to kill him and he ran away from us. But when he came to encourage us mostly Nimbalians to join his forces, that whatever Doe did to your people you should revenge and carry out the same act and what they did to us was what we did to them. We hadn't any sea port or container to put the children there or this or that rather than to go and fight against them and destroy them.

Judge Doherty: Pause, Mr Witness. The question is who told you to eat Krahns? Please answer that question.

Zigzag Marzah: I said yes sir, yes sir. I said Charles Taylor.

Defense: Very well. And did Charles Taylor order you to eat people in Sierra Leone as well?

Zigzag Marzah: Yes, sir, to set example for the forces to be afraid.

Defense: So help me, where in Sierra Leone did you eat people?

Zigzag Marzah: It happened when we were disarming the ECOMOG by his directive. He said that those Nigerians were disturbing the south eastern region, when we captured them we should eat them. Even the UN, when we were disarming them he said he didn't want any of those white people to pass through Freetown to go, so when we get them we can use them as pork.

Defense: Port or pork?

Zigzag Marzah: Pork. Pork to eat. Pig. Food.

Defense: So Charles Taylor told you you could eat Nigerians and white people as pork?

Zigzag Marzah: The Nigerian - the Nigerians and the UN. He said the remaining Africans which will pass with them through Buedu, he will turn them over to the international communities, but the others, like the Nigerians and some other people, we should kill them and do anything we want to do with them and that was what we were supposed to do with them is what I am telling you.

Defense: So, Mr Marzah, Charles Taylor ordered you to eat Nigerians --

Zigzag Marzah: Yes.

Defense: -- and white UN officials. How did he give you that order? Was it in person or was it over the radio or what?

Zigzag Marzah: It was not over radio. When Mosquito went for the first time when ECOMOG were deployed and he gave the instruction for us to go and disarm the ECOMOG he said he hasn't got any room. Even when there is no food guerrillas live by their fellow human beings, so we should live by them when had there was no food. So that was how we were living by them, by eating them. There he is sitting down.

Defense: How many UN soldiers or ECOMOG soldiers did you eat?

Zigzag Marzah: Thank you very much. The ECOMOG soldiers, the Nigerian troops, we eat a few, but not many. But many were executed, about 68. Those who were captured were executed. And the UN troops, the whites, after we had taken them to Vahun to Benjamin Yeaten's base Benjamin Yeaten himself executed about --

Defense: No, no, let's forget about executions --

Zigzag Marzah: Wait. Wait now. You can't eat them alive. You can't eat human beings alive. You have to execute them before you eat them, right.

Defense: Right. And did you cook them as well?

Zigzag Marzah: Yes, I participated. You think if my senior commander does something I will deviate from it?

Defense: So help me, please, just how do you prepare a human being for a pot?

Zigzag Marzah: I am sorry there's no way to demonstrate here because we are sitting.

Defense: Just describe it to us?

Zigzag Marzah: Okay. The way we do it, the way you're standing, sometimes we lay you down, slit your throat and butcher you and take out your skin, your flesh, throw your head away, your intestines, your flesh, we take it and put it in a pot and cook it and eat it. The way you're standing, you cannot stay like that and we eat you. We would kill you first and take those parts that are not good for us and this your palm, your two palms, we would put them together and clean inside your intestine and wrap it around, because it's not correct. It's a hard bone. Charles Taylor knows that. That's how we eat them.

Defense: And did you have a preference for white people, Nigerians or Krahns, which ones taste the best?

Zigzag Marzah: Yes, I have likeness for them, but there was no alternative to do it my own way. There was no was no alternative to do it your own way. As long as it was Charles Taylor who gave instruction and you did anything your own way you would be surely executed. If I'm lying, the remaining UN troops, the Africans that passed through --

Judge Doherty: Mr Witness, pause. You have deviated from the answer.

Defense: Now I mean that wasn't the only instant where you ate human flesh. You also ate Superman's heart, didn't you?

Zigzag Marzah: Yes, by the directive and a ceremony in Ben's yard by the time we turned over his hand to Charles Taylor.

Defense: And did Charles Taylor tell you as well to eat Superman's heart?

Zigzag Marzah: Yes, yes.

Defense: Where were you when he told you to do that?

Zigzag Marzah: Ask he himself. I can --

Judge Doherty: Mr Witness, I've told you before, no facetious replies.

Defense: Where were you when Charles Taylor told you to eat Superman's heart?

Zigzag Marzah: When after he had passed the instruction, because in his security meeting he said whatever instruction comes from Ben should be executed, whatever instruction came from Ben should be executed. Whoever does not go by Ben's instruction would be dealt with. So when we killed the men - the man and he said we should take out the heart and Charles Taylor said we should eat the heart and take the hand to him. So in my presence Ben and I entered at the back of his yard. He went inside in Charles Taylor's house and turned Superman's hand over to him and from there he gave us $200 each, went into his car and bought - he went and bought the ingredients to cook the man's heart with. That's how I believed that that was his instruction.

Defense: So it wasn't Charles Taylor who actually told you, it was Benjamin Yeaten?

Zigzag Marzah: It was Charles Taylor. It was Charles Taylor. It was Charles Taylor. Listen to my explanation.

Defense: So help me one final time because we're running out of time. Where were you when Charles Taylor gave you the instruction to eat Superman's heart?

Zigzag Marzah: At that time we had already executed Superman. We were in Monrovia with the man's heart and the arm.

Judge Doherty: Mr Witness, listen to the question. The question is about a place. Where were you? Where?

Zigzag Marzah: Okay, we were in Monrovia. In Monrovia. In Monrovia.

Defense: Where in Monrovia was it that Charles Taylor stood in front of you and said, "Zigzag, I want you not only to cut off his hand but to also eat his heart". Where were you when Taylor said that to you?

Prosecutor: Objection, your Honour. As stated the question assumes facts that the witness has not testified to.

Judge Doherty: You're being overly precise, Mr Griffiths. You're assuming that the person was in front of him, et cetera.

Defense: Was there ever a time when you stood in front of Charles Taylor physically like now and he said to you, "Zigzag, I want you to go out and eat a human being" or a part of a human being?

Zigzag Marzah: Apart from Superman?

Defense: Anyone. Anybody?

Zigzag Marzah: Okay, thank you.

Defense: Whether he be white --

Zigzag Marzah: Thank you, I understand. It happened twice when Gbarnga fell. I stood physically before Charles Taylor at the time Robin White was interviewing him. They were standing beside a jeep and he was telling the man that he was in his yard. That is the time he telephoned the Death Squad for me to carry out that execution. Anywhere there are human beings, you should eat them. They are no longer human beings. I was not in position to eat them raw, rather than to cook them with pepper and salt and fix some barbecue with them. It was from Gbarnga.

Defense: Would that be a convenient point, your Honour?

Judge Doherty: Indeed, Mr Griffiths. We will take the normal mid-morning adjournment.

The above remarkable exchange is the purest theater that real life can offer. There is drama, humour, horror, absurdity and tragedy at once. If we started out wondering who shot Superman, we are now beyond the gruesome mechanics of the deed, and deep into the aftermath, discussing not just Superman's death but also his dismemberment and consumption. Consider the defense attorney's barely disguised incredulity at the allegations of cannibalism and his dogged persistence in trying to discredit the witness and prove that his client had not given direct orders as alleged. He presses the point repeatedly: "Where were you when Charles Taylor told you to eat Superman's heart?" Consider the gusto and argumentative posture of the witness, a remorseless serial killer who also happens to be very charismatic - he gives great copy is what journalists would say, and polite to a fault (he prefaces almost all his answers with thank you very much). Zigzag Marzah is a courteous zombie by definition, and one who performs his master's demands without question. Add the Judge's interjections, and the Prosecution's objections, and let's not forget the witness diving eagerly into the discussion about the mechanics of dressing and eating humans, the willingness to demonstrate and regale the audience with recipes of pork, salt, pepper, and barbeque techniques. It is a quite remarkable performance.

Zigzag Marzah would carry on in his testimony to insist that he was just following the laws of his "poro society" and engaging in killing and cannibalism with its leader Charles Taylor - recounting several other instances when they had shared meals of human hearts or 'livers' as they would call them. Delivering Superman's hand in person to Charles Taylor was not a sufficiently final outcome, his heart also needed to be consumed. Thus a very perverse tradition of secret societies came to be wartime normalcy.

Every emotion is heightened in the transcript leading to the realization by all at the end of the exchange that everyone has been tainted by what they have heard. If the witness's victims were indeed "no longer human beings" (Charles Taylor's explicit justification for the indignities inflicted on them at, and after, death), then how are we we to classify him, the perpetrator? What did the aptly named Reflection think about witnessing these gruesome deeds? And what about everyone in that courtroom debating the issue? And what about us, the later readers of these transcripts? Well, we were all victims.

VII. The Bitterness of War

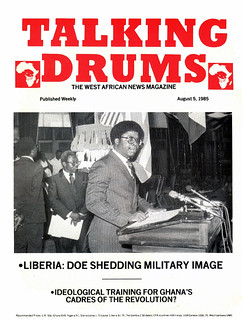

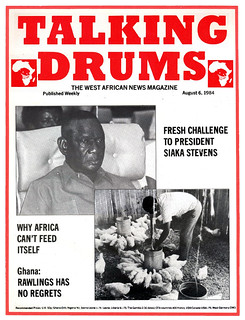

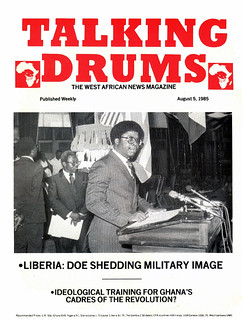

I've previously discussed the dilemmas faced by my mother and her colleagues working at the BBC's African service in how they dealt with the various warlords in the Liberian and Sierra Leonean civil wars. Were they giving these colorful and ever-quotable miscreants too much oxygen and exposure for their nefarious deeds? Were their stories "news" or was the simple act of acknowledging them making "news"? For the warlords would suspend hostilities without fail when 1700 GMT came around and the first edition of the Focus on Africa bulletin would start. They would get on their satellite phones and call the studio to see if they could get on air to discuss their dirty war. There was considerable discomfort and even guilt in the halls of Bush House.

Witness: Well, we heard that Charles Taylor and his rebels were fighting in Liberia. Then at one time we heard over the radio that he was saying that they were using Sierra Leone as an ECOMOG base to launch attacks in Liberia, so Sierra Leone will face the bitterness of war one day.

Prosecutor: Now, again, Mr Witness, when you heard this BBC programme who did you know was Charles Taylor?

Witness: Well, we heard that he was the rebel leader for the NPFL who entered into Liberia.

Witness: We heard that they were fighting in Liberia. We also heard that Taylor said they were using Sierra Leone as an ECOMOG base and so Sierra Leone will taste the bitterness of war.

Prosecutor: And when you heard this programme on the radio how did you know that it was Charles Taylor talking?

Witness: Well, he himself, when he was being interviewed, when Robin White was interviewing him, we heard his name.

Prosecutor: And Robin White, who was Robin White?

Witness: Well, Robin White was a BBC reporter that we knew about.

There was more than enough prima facie evidence of misdeeds to convict Charles Taylor, yet it was the blood diamond angle pursued by prosecutors that was the highest profile strand to the case - the glamour of Naomi Campbell proved irresistible. There is lots in the testimony about the mechanics of abductions and forced labor in mines with considerable details of the mining operations, the two pile system and the casual cruelty towards the slave labour workforce. There is a long chain of evidence leading ultimately to the trading of mayonnaise jars of diamonds in exchange for arms and ammunition.

The destructive use of child soldiers loaded with drugs and forced under compulsion of death to do awful deeds is also highlighted at length. We are in the presence of malevolence.

Defense: And how old was this child?

Witness: One year, some months. Close to two years.

Defense: You were at Superman Ground with a child of a year and a few months old and you gave your child to Sebatu, yes?

Witness: Yes

Defense: And in one of your interviews with the Office of the Prosecutor you told them that that child was essentially killed in what you said was a sacrifice ritual by Sam Bockarie, yes?

Witness: Yes

Defense: Was the child killed in 1998?

Witness: 1999

Defense: Do you know what month your child was killed in 1999?

Witness: In March...

Defense: And from the time when your child was killed by Sam Bockarie up until disarmament you have told us that you facilitated radio communication at certain times between Buedu and Superman, yes?

Witness: Yes

Defense: You were conveying messages from the same Sam Bockarie, who killed your child, to Superman, yes?

Witness: Yes

Defense: Did you ask how it came to be that he killed your child?

Witness: I did not ask, but I knew. And the person who was sent to bring the child said so. Issa Sesay too said so, that that was happened to my child. And when I saw my sister she also explained to me that that was what had transpired.

Defense: What exactly did Sam Bockarie do to your child? What do you mean by "sacrifice ritual"?

Witness: I don't want to explain further than that.

Judge: Pause, Mr Anyah. Madam Witness, you have been asked a question and you said you did not want to explain further. Why do you not want to explain further? Madam Witness, would you like a break or would you like somebody from WVS to assist you?

Witness: starts crying. Witness, however, says she is fine and will continue.

Defense: Madam Witness, you told the Prosecution not long ago this month, the month of June 2008, that Sam Bockarie killed your child in a sacrifice ritual. What does sacrifice ritual mean, Madam Witness?

Witness: He sacrificed him for power. They did not kill him. They buried him alive. From the person who did that are the person whom they sent, he told me...

There is no time to pause on the distressing stories during the cross examination, the defense simply presses on, and the topic turns from sacrifice ritual to herbalists and juju.

Defense: You spoke about some herbalists, seven of them you said, Liberians, that were sent to Sam Bockarie, yes?

Witness: Yes.

Defense: Were they just seven, or were they more than seven?

Witness: There were more than seven, but those who were heading the herbalists, those who were doing the job, were seven...

Defense: And at some point Sam Bockarie sent those herbalists to join you and Superman, is that correct?

Witness: Yes, we went and collected them.

Defense: And what was the purpose of having these herbalists?

Witness: I think I have said that before. They came to mark our bodies, like the other soldiers who were in the RUF, as a protective measure for - so that when they attack, bullets will not pierce them.

Defense: And indeed, this morning you added that the herbalists were sent by Charles Taylor, correct?

Witness: Yes.

Defense: And if what this woman says is true, then it means that the President of Liberia was sending the RUF herbalists to protect them with I think you said juju, yes?

Witness: Yes.

Defense: While fighting war, yes?

Witness: That was what he told me.

Defense: And juju is what?

Judge Sebutinde: Mr Interpreter, who is the "he"?

The Interpreter: Your Honours, it is not actually clear in the witness's answer. In Krio we do not have any distinction between a he and a she. She just said, "That was what he told me."

Judge Sebutinde: Was she talking about a herbalist, or a Gbandi woman?

The Interpreter: Well, I do not know in her answer. That is the train that is continuing.

Judge Doherty: Please clarify the point.

Defense: The person who told you Charles Taylor sent this herbalist was the Gbandi woman, correct?

Witness: Yes.

Defense: And to put my question again, if what she says is true then it would mean that the President of Liberia at the time, Charles Taylor, in 1998 was sending over herbalists to use juju, the phrase that you used, to protect RUF fighters from bullets, correct?

Witness: I said that was what the herbalist woman told me.

The discussion, which sets out on the issue of the belief system that would send herbalists to protect members of a militia from bullets, takes an unexpected turn into matters of interpretation and syntax and dives into languages that do not differentiate gender. Dialog worthy of Beckett (or perhaps Stoppard if you are that way inclined).

There are many close calls with death, especially harrowing whenever Chucky Taylor, Charles Taylor's sociopathic son was involved. Thankfully a few lived to tell the tale.

Defense: During the course of the day, one of your captures while feeding you manages to drop the metal spoon in the pit, you and your colleague manage to break the metal spoon in half and cut your bonds?

Witness: Yes.

Defense: So this is the third time you are escaping?

Witness: No the second time

Defense: How did you manage to escape so many times?

Witness: Human instinct

Defense: Why weren't you executed?

Witness: It was a blessing I had.

Note here how the witness deflects the continued skepticism of the defense attorney who tries to raise issues of credibility. This undercurrent of dramatic tension raises the stakes throughout the proceedings.

Witness: Except when you are telling me now but Sesay Musa told me that his brother was the ambassador and he was a late man.

Judge: What do you mean by he was a late man?

Witness: He said he was dead

Sometimes the testimony devolves into absurd minutiae, consider this argument about the price of pizza in Monrovia (the defense is trying to challenge a witness's credibility, implying he was paid to lie).

Defense: You could eat a lot in Ganta for 25 US dollars, couldn't you?

Witness: One piece of pizza is more than $25 in Liberia.

Defense: US dollars for one piece of pizza?

Witness: US dollars, yes.

Defense: Hang on.

Witness: Yes, yes, pizza, yes.

Defense: Hang on. Wait for me to finish the question before you start interrupting and laughing. Are you seriously telling this Court that a piece of pizza in Ganta costs more than $25 US?

Witness: In Monrovia, not in Ganta. Monrovia. Monrovia. Yes, in Monrovia. And I can locate the areas to you for you to make a background investigation.

Defense: So it would cost more than the rent of one of your motorbikes for a whole day just to eat a piece of pizza?

Witness: When you bring me to Monrovia I would have to eat, eat good food, yes, but from the money I get from my motorbikes I cannot take that to go and buy pizza, but in Ganta I eat what I eat, but at any time I come to Monrovia when - I eat what I want to eat because like I'm here, they brought me here, when you bring me here you have to feed me. What I want to eat is what I ask for, it's what I eat.

Sometimes there are moments of levity although they are quickly challenged.

Defense: If you look at that document in the middle of the page, paragraph 2 says: "Subsistence allowance. Witness: was brought under the protection of the Court on 20 August 2006. To date he has been paid a total of 13,122,800 leones."

What is amusing you about that?

Witness: Nothing made me to laugh about that. It is just my usual habit. I am not laughing. I am chuckling.

If the defense would challenge many of the witnesses, in all too many cases it would be inhuman to question the overwhelming evidence that was being presented against their clients and so the summaries would end: "the Defense had no questions for this witness".

Ultimately, the rebel commander ordered a boy no more than 13 years-old to cut off the witness's arms. After his arms were amputated, the witness testified that "Rambo" arrived at the village, and he was angry with the rebels for killing some civilians and amputating the limbs of others. The witness reported that Rambo gave him money and told him to endure the pain, because that was what God had ordained. The witness testified that before the amputation he was a petty trader, but that since 1999, when this incident happened, his only source of income has been begging.

The Defense had no questions for this witness.

VIII. Reflection

The machinery of the law works slowly and despite my stance of permanent outrage, I've often thought that this slowness, this bureaucracy, was a good thing. It is an antidote to rushed judgement and an aid to careful reflection on tort and damage - collateral and intended. I expect that lawyers are still interrogating Slobodan Miloševic in whatever part of hell he is - his five years facing trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia were clearly not enough. Similarly, Charles Taylor's comfortable jail library ought to consist solely of these trial transcripts.

And yet the trial setting can be a little unsatisfactory for the historian or cultural observer whose intent is to plumb the depths of a tragedy for psychological insight. Memory is difficult - the recollection of often traumatic events can lack coherence. Defense lawyers can seize on the smallest inconsistencies to raise doubt. Prosecutors have to show certain facts as they lay out their case and oftentimes, they stick to a limited brief. The distinction between what can be proved and what actually happened is a sharp one. We have to balance our desire for a full accounting against the right of defendants to have a fair and public hearing and what can be proven in a court of law.

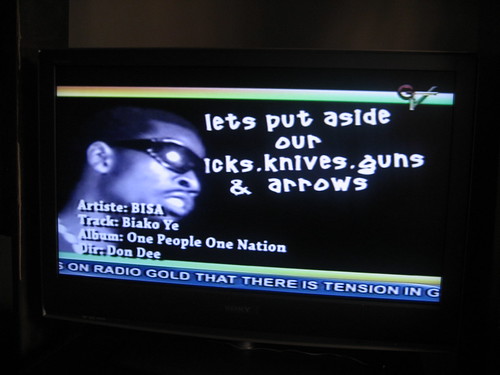

I've focused mainly on one thread in reading these transcripts, the cautionary aspect (with occasional diversions into the absurd journeys that language can take one on). And it is this notion of caution that keeps me at night whenever I've seen the signposts of political violence raised in my own country, Ghana. It leads me to be a scold of sorts and to engage in jeremiads. It is worth emphasizing that it didn't take much for things to fall apart in Liberia and Sierra Leone. It took just a few well-connected rogues with a willingness to do their worst. Charles Taylor, Foday Sankoh and company numbered in the dozens when they started their campaign of confidence artistry, terror and conquest. Their sheer bloody-minded will, a will that went beyond any animating ideology, found fertile ground in the intrinsic cracks in Liberian and Sierra Leonean society and caused a thoroughgoing disaster whose after-effects still reverberate decades later (think of the response to the current Ebola outbreaks).

There are many more lenses through which to view the violent conflicts outlined here. An equally fruitful reading would focus on the rogues gallery jostling for the loot and influence - an international cast of Liberian and Sierra Leonean warlords, Guinean adventurers, Gambian, Ivorians and Burkinabe meddlers, Senegalese, Israelis, Libyans, Syrians, Lebanese, Saudis or, more broadly, 'the Arabs' as the locals called them, Belgian diamond traders, Bulgarian financiers, Slovenian weapons smugglers, Italian mafioso, psychopahic teenagers with identity issues, ex-CIA officers, Australian mining companies, Swiss bankers, US rubber (and robber) barrons, quiet American country preachers such as Pat Robertson and Jesse Jackson, and even the ostensible good guys, the Nigerians and Ghanaians who formed the bulk of the ECOMOG regional peacekeeping force but whose senior officers often took the freelance war profiteer route. As in Angola, this conflict did not happen in a vacuum. The evidence is there for the careful reader.

By and large, the prosecutors efforts to gain convictions for the wider strands of this joint criminal enterprise were frustrated. On the other hand, unlike the Indonesia depicted in The Act of Killing, not everyone is walking around with impunity years later. There has been some measure of justice in the proceedings even beyond the convictions of a few like Charles Taylor. True, many others have escaped accountability, but, certainly, no one is celebrating their wartime acts and appalling behavior, the perpetrators have been chastened. And if the palliative of truth and reconciliation commissions and international trials is not an effective cure for the damage inflicted, it is cathartic and, at the very least, a step in the right direction.

As Theodore Roethke put it in his celebrated poem:

In a dark time, the eye begins to see

Our novelists have found fertile ground in the soil of this conflict but their creative works needn't stand alone. The stories leap out of the pages and therein lies the enduring legacy of the Special Court on Sierra Leone. I find comfort in the shadows of these trial transcripts. The stories they outline cast a light on modern Africa, unvarnished and denuded of any imputed childlike innocence. While we set about strengthening the cement of our society, let us have no illusions about our frailty. As we pursue the mundane work of development, let us be vigilant in safeguarding our bite-sized triumphs for, ultimately, the game of the rough beast is about who is writing the script. And so I'll write my own script.

Soundtrack for this note (listen)

Index

Previously in Part I: Close Encounters

Next in Part III: Enter Doctor Simbo

See also:

Naming Conventions

File under: Sierra Leone, Liberia, Africa, war, civil war, language, law, trial, culture, observation, perception, reading, drama, tragedy, literature, review, memory, politics, history, rogues, blood, violence, murder absurd, The Rough Beast, Things Fall Apart