Uncle Mike

A man in full, in 10 movements...

I. Funeral Minded

Islington crematorium

Webcast, funeral-minded

Brave daughter

Minor speeches

Quarrelsome Uncle

Fond arguments

Fugitive memories

In loco parentis

Distant grief

Transatlantic sorrow

The pastor's gloves

The absence of hugs

Murmurs of mourners

Social distancing

Brutal efficiency

Death. Finality.

II. The Shape of an Argument

He relished an argument, for better or worse. He loved the reality of a quarrel. It could be infuriating, and wearying for sure, to become embroiled in one of his affairs. More often however, it was fun. You'd notice the twinkle in his eye as he launched into things, you got to learn the shape of an argument. Oh the quarrels, Uncle Mike. We still shake our heads.

His method wasn't didactic and it certainly wasn't socratic. He got down in the trenches, he would fight dirty when he argued. He'd bring in humour and all the considerable charm, or alternately, the gravitas, that he could muster even while marshalling the most esoteric theories. It was an equal opportunity free-for-all with him. The youngest of children, and adults alike, were targets and compères in these arguments, and that was the liberating aspect. We'd argue about everything, in broad outline, and in minute details. And with panache. Our poet, Kwesi Brew, might well have had Uncle Mike in mind with his line about whether to "engage the scarlet fury of battle". My Avu knew all about Ghana's Philosopy of Survival.

He made you articulate, clarify, and revisit your point. And when he realized that he was on the losing side of an argument, which was all too often, he'd switch, and pretend he'd been playing devil's advocate all along. Of course, this tic was a ruse, he was merely biding his time while thinking of a better riposte. As you finally let your guard down, he would pounce. Cue the twinkle in the eye, the arched eyebrows, the raised voice, and those phrases: "Obviously... You know as well as I do... That's a foolish argument... Foolish...". Yes, foolish.

We'd move from room to room during all this, or sit outside in the garden under the frangipani tree or next to the indestructible yellow Fiat. The obligatory beer would be in hand, the belly laughs would erupt as daily absurdities were explored - and Ghana in the 1970s was a petri dish of all manner of absurdities. He had strong opinions for sure, but, crucially, he wanted to hear yours - if only to dismiss them heartily. This was where the love of strange bedfellows and the journalistic impulse was cultivated. This was where I learned about toli, about 'filler', about seeking the story behind the story. He would indulge our exploration of the issues, in sports, politics, economics, and all manner of small things and kindred subjects. It was infectious, and I was happy to be infected by this searching compulsion.

And yes, he was a Larteh man, through and through. Uncle Mike was a man of big appetites; fufu and abenkwan and riotous conversation were his primary vices. Being an uncle in Akan society confers more obligations even than being a father, and he took these things seriously. Any number of children all over Accra and Larteh were his charges, to be supported and nurtured - sometimes (and we complained bitterly at those times) to the detriment of his own brood - the complaints were brushed aside dismissively ("Foolish"). A generous spirit, he made sure, after the intense daily conversations had run their course, to sponsor all the neighbourhood children to walk down to Auntie Becky's at Labone junction for kelewele and peanuts. His was an open house in every way.

The hedge that separated our houses on Soula Loop might as well have been blades of grass.

III. A Heavy Coat

Uncle Mike was the last person I saw at the airport the night we fled Ghana, mere weeks after the coup in 1982. His was the last friendly face to sear my memory of Ghana for the next decade. Earlier that night, he had handed me the winter coat, a man's coat, that I would wear over my school uniform. He succinctly explained things to me - Mum and I were leaving, he had to count on me, that Mum depended on me. And before I set out in advance to the airport with Uncle Emma, he indulged my last meal: Cerelac - a detail he never let me live down even decades later. Later that night, he drove Mum in that seasoned Fiat through all those checkpoints on the normally short journey from Labone to Kotoka, leaving at the very last minute, and carrying very little. The cover story, after all, was that we were simply attending that three day conference in Holland as previously arranged. He shepherded her through the airport, brazening the revolutionary inquisitions with all his hearty charisma. His sharp look silenced me when I saw the two of them haggling at the desk just outside the duty free shop, and I resisted the urge to run up to her. He was my comfort suite in that still moment, then and as ever.

The heavy coat would come in handy in Amsterdam when we arrived the next morning, and in the years to come (I wore it long into my teenage years). My 9 year old self was swamped by it in the cold of Schiphol airport for those long hours when we paced the walkways of the airport, waiting for the next development. Who did we know in this town? No one was expecting us despite our bravado. Would we be wards of the UN or Amnesty International? Should we request asylum? Would we be sent back? We had packed light, and had left with nothing (in any case, any foreign exchange would have been seized on our way out - revolutionary saboteurs you see). Our new lives beckoned full of uncertainty. The heavy coat was my blanket of soul.

In later times, I would learn how dicey things had been and the full peril of those days and of that night, that it could all have unraveled if any one thing had happened differently. The few photos I have of my childhood are those Gee and Uncle Mike managed to salvage from our house before the soldiers arrived and did their thing. Uncle Mike would recall how, years after our departure, he had met that selfsame lady who had tried to prevent us from leaving Ghana that night at that desk, in exile herself in cold London. "Revolutions have a tendancy to eat their own" was his comment to her. Indeed. A typically astute Uncle Mike bon mot.

My last memories of Ghana: first the handshake, and whispered encouragment delivered with a reassuring smile, a bear hug and the strength of his embrace. I had the coat on, even in the harmattan heat, as I walked onto the plane.

The dictionary definition of avuncular ("suggestive of an uncle, especially in kindliness or geniality") seemed written for my Uncle Mike. Avunculus was the nickname. Avu for short.

IV. A Stinging Pen

Uncle Mike liked his satire savage. In print, his biting words left a lasting sting. Friends were not exempt. Cameron Duodu would forever recall that column and that metaphor. Unearned for sure, especially as you read the details of the charge, but memorable nevertheless. The same could be said of countless others targeted by Yeli-Yeli's columns.

He was a journalist by training and inclination, one of the first graduates of the school of journalism at Legon. His avocation was to the crafting of bracing words, and he obliged at the Daily Graphic and elsewhere throughout his career. But he would branch out later from journalism into communication and public relations. He understood the power of words and was fearless in noting their implications. Hypocrites were always unmanned by Uncle Mike's forensic examinations.

There is a thin line between the fractious and the satirical. Both outlooks stem from a fundamental unhappiness with the state of the world. And it is a hard path to navigate, If Uncle Mike could always call on his innate joie de vivre as his font of optimism, he remained unhappy about the state of Ghana, of Africa and of his people. No matter the situation, like my mother, he was a firm believer in the necessity of permanent outrage.

I have a theory about the many Africans who have had to deal with being political prisoners over the years. Not everyone will come out the way Nelson Mandela did, serene and resolute. Many are broken for sure, the humbling of confinement exacts a heavy toll on one's faith and fortitude. The majority are equanimous I suppose. But many also come out having inherited a wilful streak from their captors. They never look back, and their convictions, or indeed their decisions, will not be challenged come what may (think Mugabe, think Nkrumah in the Ghanaian context). Uncle Mike landed towards the latter end of the spectrum after his experience. And it's worth explaining...

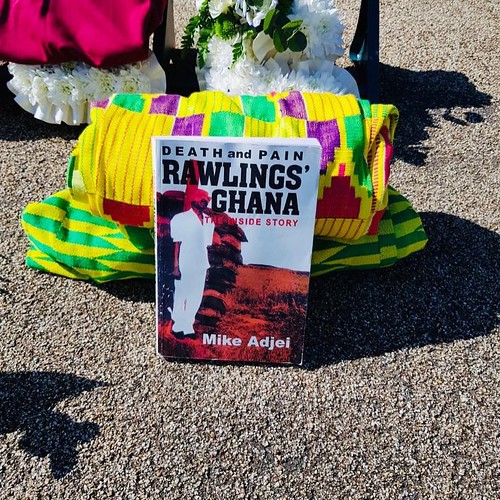

Death and Pain: Rawlings's Ghana was the name of the book he ultimately published, his memoirs of those years. You could quibble with some of the details, hell Uncle Mike would encourage your arguments, and he wrote it in a typically discursive, sometimes gossipy, and always polemic manner. But, well, like with everything he wrote, the kernel of truth is there, the facts will not be denied. And, like the book's title, the facts and the words sting, and linger in the mind.

There was that mild column that he wrote. It did contain a milquetoast critique of the Flight Lieutenant and his regime. Trigger happy men, they did regularly summon journalists to The Castle for not being complaisant. Uncle Mike's body did bear blunt witness to their pettiness. The soldiers did come for him at the house. Multiple times. They did come with heavy boots and knocked down doors searching for him. He was savagely beaten at Gondar Barracks. The soldiers did bundle him up to Nsawam prison. He did spend almost a year in detention without charge. He did witness all manner of pathologies of those strong men in military garb.

He would recount his reception with the grim faced souls he met at the camps. "Talk true!", they would shout before welcoming him with dirty slaps and worse. The mock, and the real, executions did leave their scars. My cousins and aunt were indeed terrorized, nay traumatized, for all those years. Uncle Mike did have to flee into exile after his release, first to Nigeria and then, at length, to the United Kingdom for fear that the worst threats to his person would be realized. The occupants of The Castle did order and sanction wanton brutality, and let's be frank, murder was their close companion in their so-called revolution. And they did write amnesty provisions into our constitution to immunize themselves after all.

There is truth, and there is reconciliation for sure, but I have no patience with those who acquiesce with their now decades-long rehabilitiation campaign. Forgive my visceral reaction, it's the blood you see, I have no immunity.

They, the names are familiar to Ghanaians, the Rawlingses, the Tsikatas, the Botchweys, had all been in our North Labone houses, drinking the same Star and Club beer, and arguing with everyone else under that same frangipani tree. No one was happy with the state of Ghana in the 1970s. They had babysat us children, and we had babysat their own children, our playmates in those lazy streets. The Flight Lieutenant liked to take the more intrepid of us horse riding. If Uncle Jerry (or was it Uncle Kojo?) was displeased at something Uncle Mike had written, and had decided to teach him a brutal lesson for those unkind words, why did no one intervene? For that year, when Gee would make the rounds, braving curfews, to The Castle and the now-fortified houses that our former friends, uncles (and aunts) lived in, to plead for news of the whereabouts of her husband, for the return of their erstwhile friend, why did they not intervene?

It doesn't bear answering. The best that can be said is that, perhaps they thought they did their part and they prevented his death. The worst, a combination of cowardice at unchecked wrath, and casual cruelty, is that they approved. The blood had simply gone to their heads. They had conquered a country, after all, and they liked sitting on the throne. All was permitted and all was done, to their eternal discredit. The question is unanswered.

I turn again to the poet

The nature of the human heart wreaks its mischief

Upon close neighbours each smoldering with his own craving.

From unfulfilled desires burst forth consuming anger

Uncle Mike left you in no doubt where he stood, and who he was rooting for. He survived all this revolutionary justice and more. And it is in this spirit, and in his stead, that I offer the next movement.

V. The Wages of Thermidor

I did not have to wait

For the distance of history in order to pronounce judgement.

For theirs is a legacy of bloodstains and unnecessary suffering.

And it was scarred on our stunted bodies in real time.

The jagged marks of their chains endure.

Venality without compromise,

Wrath without provocation,

And vitriol as compensatory cover.

Neither do they deserve the nuance they denied others

In their unseemly haste to spill blood on the earth.

We noted at the time their pecuniary motives

Those strutting peacocks in khaki uniforms

Extorting bribes as they went, in exchange for curfew passes

Score settling amidst an orgy of common thievery

The rhetoric of grievance

Couched in class resentment

But masked as the moral midgetry of thin-skinned men.

I had a dream

Of tyrants destroyed

With all available indignities.

And when the voiceless sphinx awoke

It was to an unvarnished vision

And an unbidden gift:

The welcome irrelevance

Of that baleful cohort

Their evanescent stature

A fugitive reality

And all this happened

Almost imperceptibly

Their dreadnought weight lifted

For such are the wages of Thermidor

VI. Avunculus, a playlist

A musical interlude, a break for beer or something...

- 8 Million Stories by A Tribe Called Quest

- 992 Arguments by The O'Jays

- You See the Trouble With Me by Barry White

- Fear not for Man by Fela Kuti

- Trouble Man by Marvin Gaye

- The Star of a Story by Heatwave

- Unanswered Question by Amel Larrieux

- Arguin' on the Funk by Digital Underground

- Double Trouble by The Roots

- Tell me a Tale by Michael Kiwanuka

- Trouble by Jose James

- Even After All by Finley Quaye

- Trouble by Amel Larrieux

Quoth the soul singer

Some people got that (je ne sais quoi)

I don't know, where you just have to look back (two times, two times)

A walking invitation into the fire

Or higher ground

A mystical combination (it's like, it's like)

VII. Double Trouble

I suspect I shouldn't go there, and I hesitate in writing this next section, but, well, my Avu was a complicated man. Further, I was the one that got the call that unraveled the deception, so here goes...

I was home alone from school (or was it university?) one day in the 90s when I received a phone call from the UNHCR. The woman was calling from Heathrow airport and wanted to find Uncle Mike because his two children had arrived. She wanted to confirm the details. Our house had been Uncle Mike's first port of call when he made it to exile in London but he hadn't been staying with us for quite a while. A small flat in Brent Cross will never compare to what we had left in North Labone.

I couldn't imagine my cousins leaving without Gee, my aunt. Further, I had three cousins in Ghana not two. How could Nii Okyne have been left behind? Or had my Tatu stayed with Gee in Ghana? And then there were the names she provided. Had they had to use aliases to get out of Ghana? And the ages didn't match up. I was completely bemused, befuddled, perplexed. I had spent my entire childhood with my cousins. I knew and was raised by my uncle - in loco parentis was his catchphrase with me. What was going on? Who were these people at the airport? Was it a case of identity theft perhaps? Our compatriots were getting creative in their quest for exile in this era of the Scramble for Babylon. Or was the Refugee Commissioner looking for another Uncle Mike? I was conjuring up scenarios as we spoke.

At length, it dawned on me that it was indeed the same Uncle Mike, but that there was another family. I mumbled my own cover story to salvage the conversation with my interlocuter, professing confusion and a bad memory, "I haven't seen them in years... I think you have it right... ". I was shaken when I put the phone down. I had to steel myself to narrate the call when Mum returned after a long day at Bush House worrying about the vicissitudes of Mother Africa for the Beeb.

So. Another family...

The recrimations were immediate, and the battle lines were drawn. The hurt was a simple fact; the betrayal was complete. The hurt, like our newly discovered brethren, could not be denied. All those discussions of loyalty, of equity, of betrayal, of justice, of love, of innocence, and of our core identities were brought into play and revisited anew, and with new eyes.

If our exile in London was a dim, grey struggle, we Lonely Londoners had it easier by far. We were the success stories of Ghana must go. The deprivations that our family who had stayed back home in Ghana were facing were unsurmountable. It was frankly brutal on Gee and my cousins, I had seen as much in my two brief visits. I remember being embarrassed by the relish with which the few tins of corned beef and sardines I had shoved in my hand luggage had been received. Not to mention the avidity with which the dusty books and old magazines I had casually discarded were taken up. Ever since I've always made sure to pack a suitcase of reading material when I go home - the need is still there. There was no way to sugar coat it. Ghana in our lost decades was was all about privation and suffering and Uncle Mike had written the book about it. How come, then, that they weren't the ones being brought out of darkest Africa?

We never talked about this trouble, Uncle Mike and I. But I don't think that there was ever shame. It was just one of those things in the affairs of men and women, a fugitive glimpse at the naked world. We, all of us, simply reassessed the complexity of said world. I was surprised at how quickly we all made our accomodation to the new reality. Family is family, and we embraced our new siblings and mother. For his part, Uncle Mike's door remained open throughout. If there was hurt, the soothing balm was time. If there was now distance and reticence, it was all to be acknowledged, and he was straightforward about it, and accepted his responsibility. But the conversation would continue apace. It would never stop, it could never have stopped. After all, who could ever resist arguing with him?

So. A greater family...

The lessons imparted by Uncle Mike's troubles went something like this, a balance sheet of the affairs of man:

Structural Adjustments

An early lesson learned in matters of accounting

Is of a balance sheet in the affairs of man

Revolutionary justice tips the scale, leaves borrowers overextended

The heart is prone to default on all those payments due

And so be wary of blank checks made out to an exiled soul

Broken hearts heal in the embrace of experience

Resist nostalgia and all its seductive comfort

But hold on to the clarity of your convictions

To finance the trade deficit of unanswered questions

For indeed wist is the favourite currency of love.

Above all, in all things, remember this:

Flesh and blood are not inconveniences

To think otherwise is to surely forfeit one's spirit

We can afford the taxes due on dividends in kind

For love is the defined benefit of soul insurance.

VII. Exuent

He plunged right back into politics when he returned after the inauguration in 2001. Ghana's real return to democracy after the questionable elections of the 90s (the first dubbed the Stolen Verdict, and the second "Free and fair, free from fear"). Mr Kufuor knew him as a powerful communicator, and wanted him to help style the message, just as he had for Victor Owusu. It should come as no surprise that in his writing and returnee life, the polemics and jeremiads continued apace. He was nothing if not consistent in that respect. Still, the past twenty years have been of redemption, of catching up and making up for those lost decades. He embedded himself firmly in the mountains of Larteh. It has all been about family, and it has been good.

Uncle Mike suffered a stroke last August in London. My cousin Ansaa left everything behind in Ghana to come to Babylon to take care of him. She lived out of a suitcase in his hospital room ever since, only occasionally retreating to the flat in Barnett. We heard all about the intrigue at the hospital - some thought she was his mistress, not his daughter! She organized the entire ward, the nurses and doctor alike, around Uncle Mike. Like her father, everyone knew when Ansaa was around. Everyone was drawn into her Ananse web and would summon the kotokious laughter and love that she inevitably elicited. Like father, like daughter.

I spoke to him a few times since then on WhatsApp in those hospital rooms. On Christmas day, it was particularly hard to see him so physically diminished, but he was recovering, and the twinkle in the eye and the warm smile was as strong as ever. As he got better, he got back to giving us "filler" and running commentary, holding court on nothing and everything. He had long experience of rogues like Trump and Boris Johnson and much prime material to contemplate: Brexit, impeachment, the rigged world. By New Year's Eve, the hunt was on for a place at a rehabilitiation center. Sadly the dysfunction that a decade of austerity had wrought with the NHS would raise its spectre. At length a bed was found - they needed to free beds, worried as they were about being swamped by the imminent onset of the coronavirus pandemic, and he was indeed transferred. The sanctuary this dutiful taxpayer of Her Majesty had every right to expect turned out to be a bed of novel coronavirus and he succumbed within days to COVID-19.

If Ansaa makes it through the weeks of her covidious quarantine, Uncle Mike's ashes are destined for the hills of Larteh. Along with pieces of my heart.

IX. Blues and Roots

"The man who watches and waits, the man who attacks because he's afraid, and the man who wants to trust and love but retreats each time he finds himself betrayed."

— from Beneath the Underdog, a memoir as quoted in An Argument With Instruments: On Charles Mingus

Uncle Mike was just my uncle. But he was also an artist, an artisan of prose. The adjectives to describe him, soft yet prickly, argumentative yet imbued with delicacy and craft, resonate with those about that big bear Charles Mingus. The musical analog of this beautiful, fractured and fractious soul is to be found in the combativeness and virtuosity of the first four songs of Mingus' Blues and Roots album. The titles tell the tale by themselves, and the music remains immortal:

Listen well, they tell a story.

Further reading

X. Grief, a playlist

- King Of Sorrow by Sade

- Numb by Portishead

- How My Heart Sings by Bill Evans Trio

- Resolution by John Coltrane

- Weary by Amel Larrieux

In memory of Uncle Mike, in loco parentis.

I nominate this note for The Things Fall Apart Series under the banner of Social Living.

File under: memory, family, appreciation, loss, Ghana, culture, observation, perception, politics, life, death, coronavirus, poetry, coup, exile, immigration, Africa, obituary, Social Living,Things Fall Apart, toli

No comments:

Post a Comment