African Ceremonies

I give you African Ceremonies, my photographic examination of some of the ties that bind us in Africa and the diaspora...

Back in 2006, I gathered some photos I'd taken into a slide show about African ceremonies. It was intended as a companion piece to an article I was writing about building software to support communities and how to highlight the periodic social events that all communities require - said article has sadly remained dark matter. Well that's my cover story, another theory is that I had 15 minutes to procrastinate...

A curious few who happened onto the photos asked for a little narration to underline what I was getting at, and to explain some of what was taking place, the traditional weddings were intriguing it seems. There was also a withering comment about why I labeled it "African" rather than the more specific "Ghanaian" - but I'll dodge that one now as I did back then. I was vaguely hoping to start a trend and was hopeful that others from the continent or diaspora would add their own visions of their own ceremonies. I was early on the web and, for the longest time, if you searched for Ghana weddings, my happy day would have been your top search result (sidenote: a lazy Ghanaian journalist once did that search and used one of our photos to illustrate a story about sham Green card marriages which almost gave my poor mother a heart attack as she opened her newspaper one morning to see her son and daughter-in-law in glorious print and juxtaposed infamy - I really must dig up that paper from my archives).

I am well aware of the types and faces that we traditionally see of Africa. I've been pleased, in the years since, to see Africans adopt Flickr, Instagram, and what have you. As internet penetration advanced, and especially with the adoption of mobile phones, we are all putting out our own images and telling our own stories. Here comes everybody, as a prescient Clay Shirky intoned.

There is a tension however about putting one's family snaps out there, I am mindful of privacy concerns that may arise and have taken down promptly whenever alerted. I've found though that my loved ones have actually appreciated my amateur social historian impulses and the value of a simple link. Even when I've recorded painful interludes and genuine grief, the memories of our rituals and traditions have been the social capital and comfort that we draw on to go forward.

Then the pandemic intervened and, in this covidious interlude, I've had further time to pair all those images with a very special piece of music, a stunning version of Better Days Ahead by Gil Scott-Heron, recorded Live at the Fox Theatre Boulder Colorado in 1979, I believe - hat tip to Kalamu.

Herewith then an attempt to turn my amateur snaps into a "photo essay", a personal tour of African ceremonies...

- African Ceremonies - a photo essay

African Ceremonies (Better Days Ahead by Gil Scott-Heron)

I also give you the linked video for viewing and listening pleasure. My liner notes follow below. At the very least, the music should be your blanket of soul. I found the juxtaposition of the images and the song moving for, even as I contemplated how things have fallen apart, I could harken back to these mementos of togetherness. It is no article of faith to expect that there will be better days ahead even as we ask: what paradise have we lost?

African Ceremonies (Better Days Ahead) with Gil Scott-Heron's accompaniment

Perspectives

People like Angela Fisher and Carol Beckwith make coffee table fodder out of photography books like African Ceremonies and Africa Adorned. Those books are visually wonderful and they deserve all the acclaim (and money) they get. To my eyes however, their approach is a little too stylized; there's a loss of social and cultural context, and a sense of titillation. They omit the Coke bottles or cans, the white plastic chairs, the satellite dishes in the background or the goat-herders with the cellphones.

"Move that away", you almost hear them demand as they take the "authentic" photos. The end result is based purely on an aesthetic sense (albeit a very acute sense) and a view from the outside-in. Still I'm grateful that someone is documenting these affairs; so much of Africa's past has been ephemeral and lost in oral tradition. But the result is otherworldly and, I hesitate to bring up the word, exotic...

You don't need to point to the nativist stylings of Leni Riefenstahl whose penance for the Third Reich propaganda was a retreat to the most "traditional" Africa and a celebration of the Nuba of Sudan. It's a very different feel from the photos of African photographers like Seydou Keita or Malick Sidibe which are full of knowing wit that comes from breathing in life in the society.

This is also true if you monitor contemporary photos about Africa. The aesthetic of many of the photos in the Images of Africa pool at Flickr is quite different from that of those taken by "the locals" even if said locals have begun posting to that and other forums. This is understandable, holiday pictures of a safari, of wildlife, or of those who put on performances for your benefit will obviously be far different from the kinds of things you notice if you were involved in the occasion. Still as more Africans add to the collective pools, things are changing. The aesthetic of the more professional local photographers, say the "African Futurist" or say Blackwize is as vibrant as can be. I'm not a visual person, but whenever I've ventured into Instagram and such, I've never been disappointed. You can get a keen sense of the modernity and normalcy in their visions.

Tradition

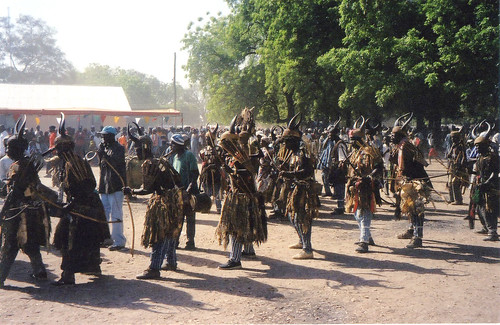

Take a ceremony like this, from Sandema in Northern Ghana (of which I'll later share a quite harrowing story).

The setting is the Feok Festival of the Builsa people where they re-enact the story of how their ancestors fought off the slave raiders. If you're ever in Ghana in December and can make it up north, you'll definitely enjoy the occasion: the elaborate choreography and exuberance of the warriors showing off their forebear's proudest moment.

Note if you will the Adidas and Nike trainers - how inauthentic, right? Angela Fisher would surely make them get some real hunter shoes, savanna grass and antelope hides or what have you before taking her photos.

One of the backstories to the photos is that these guys are all ex-policemen despite their posturing as "traditional" warriors. These days they settle scores with AK-47s instead of the cudgels and shepherd's crooks they carry here. Capturing them on the one day of the year when they ostensibly forgo their hair-trigger militia tendencies misses half the story. In many ways, they are seen by the rest of the country as a lost cause, almost akin to the Somali warlords - i.e. people to be mostly ignored or, at best, bought off to keep quiet. A quite dangerous state of affairs, but that's another story...

Pageantry

We do like our chiefs and the pageantry that comes with durbar rallies. Throughout our history we have put them on a pedestal or palanquin.

Durbars and the ceremonial umbrellas that accompany them are a recurring motif in our art.

But that is because everyone likes to dress up for parades

There's always a commotion when royalty, loosely interpreted, arrives on the scene.

We love marches and carnivals.

Grown men become supplicants when chiefs arrive at an event

It's the hint of black gold

The Agotime kente festival is another wonderful and picturesque occasion when the entire town comes out to celebrate their master weavers. You can tell how important these few hours are to community.

The Dipo ceremony of the Krobo girls is one of those rites of passage that wouldn't be out of place in coffee table books.

Knocking

While I like these glamourous and photogenic ceremonies, they are fairly infrequent. The majority of my experience of ceremonies has been of the more personal variety, and not quite so dramatic: births, engagements, weddings and funerals... Ceremonies are rites of passages and have importance in our communities given the impermanence and fragility of life in our part of the world.

Let's start with an engagement ceremony - or "knocking" as we call it in Ghana. In our traditions this is where the two families ostensibly meet for the first time.

The man's family goes bearing gifts to the woman's family to "knock" on the door, introduce themselves, declare intentions and ask for woman's hand on behalf of their son. Basically it's the traditional wedding.

Sometimes for the more showy, you can hire carriers, a band or people - color-coordinated of course, to carry the gifts your side is bringing to the table and to come and sing praises. On the whole though it's an opportunity for the families to get to know each other. Depending on the tradition, attendance by the couple is optional, this is all about the two families becoming one.

More often though, you carry them yourself.

In the Ga tradition, the groom's family arrives at the gate of the bride's father's residence and "knocks" requesting entry. Typically you offer a nominal payment of 100 cedis (about $10) for entry.

You're making an entrance. In some traditions, there is a big to-do about the entrance. They won't let you in, pretend no one is there. Or the reception is grudging, "who are you people?". But it's all a theatrical pose.

I know that in some traditions they bring out multiple ladies from the house and theatrically ask that you identify the desired, to see how well you know her. We come bearing gifts whether Schnaaps, cloth, jewelry, suitcases and cash. Gifts are symbolic although there is much ado about the list - e.g. approx 100 cedis ($10) to enter the gate, a suitcase for the woman's belongings, pieces of cloth, a ceremonial white bible, a few crates of drink, a stool etc.

We have spokesmen, or Okyeames, recounting the praises of the participants, using very ornate and flowery language. "Our son has spotted a beautiful rose in a garden." Knocking ceremonies, are mostly run by women, and indeed are for women, attendance by the men in optional.

One last thing: this was also the point at which one would openly discuss the lineage and antecedants of the couple - e.g. in the past this was the moment at which we checked with the family elders to prevent inbreeding.

Sometimes you get priests running things - with Ghana's new Christianity, you get a lot of prayer interludes. Occasionally it's silent prayer but often the exhortations are quite intense - and lengthy.

There's lots of fuss about the little things, the white bible, the ring, the cloth, the cakes, the little envelopes stuffed with cash bribes for members of the family,

the suitcases (sometimes a brand of suitcase is specified).

Sometimes the setting is quite fancy.

At other times, it's more casual and modest.

You have the families facing each other.

I'm often to be found dealing with logistics in these events

Being behind the scenes means that I can catch the little moments.

One year, you're relaxing in the background after working for days setting things up for the occasion.

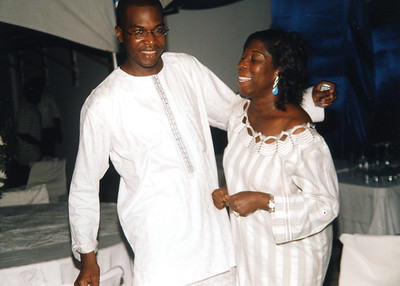

Six months later, it's your turn, and it's a case of pre-event jitters and last-minute butterflies.

Eventually we manage coax a smile out of you and you know you'll be beaming when the deal is done.

Now I shouldn't joke about these things since I'm certainly not immune to them; when my time came I had the jitters too.

Even though I knew what the result would be.

The people who come bring a lot of energy to the gathering. You may not see them often during the year but they want to affirm their membership in your community (I realize I'm writing here with software engineer's terminology, but you can sue me, my life informs my work).

Some come with glint of mischief in their eye, or maybe a sense of the cantankerous.

and perhaps pearls of experience

We all make an effort to dress up for the occasion.

Our seamstresses are kept busy

Lace style and pageantry is in order

As are the kente stylings.

Funeral Minded

The iconography of funerals I've attended rhymes with that of engagments. Even in our moments of grief, tradition demands surety. Consider an Abutia clan funeral ceremony that takes place the day after the burial. The clan visits the bereaved family bringing gifts to commiserate, bring comfort, and share in the community's loss.

There is much singing and improvisation

It punctuates the family meeting

The music is a necesary soothing balm that is missing in our current zoom funerals even as some restrictions are beginning to be lifted.

It was a painful moment for all of us, we had lost Da but you can see the exact second when my Aunt's grief was sublimated and she lost herself in the dance, in fond remembrance of her mother.

You're always surprised about who is most involved in the event. The dark matter of communities surfaces at such times. These social events are about participation and identification. Formalisms like invitations are a little much in Ghanaian traditions. If you hear that so-and-so has a baby or is getting married, it is your obligation to show up. You can imagine the uncertainty this causes. If you're organizing such an event, you should probably double your expectations about attendance. Like the South East Asians, it becomes a numbers game.

During our years under military rule the only outlet we had were these ceremonies, and once democracy returned and a middle class began to reassert itself, there has been a burgeoning industry of event planners. We believe in textiles, food and such.

Funerals are a big part of Ghanaian life although they aren't much photographed. Back when party politics were banned, the only real social occasions that mattered, and that couldn't be controlled, were these traditional ceremonies. I hope some anthropologist does a study of the funeral culture of Ghana. Economists also would have a field day: entire industries have sprung up that deal with the financing of funerals and the strategies for avoiding bankruptcy. Given the other strains on mortality in our society, funerals are a growth industry even in a covidious time.

We wear different colours - darker cloths typically black, red depending on the age and status of the person who died.

Members of the family and close friends would wear the same print.

It is well known that the Ga have made an industry, and art, out of their coffins, and well entrepreneurial spirit flourishes where there is a need.

We also mark the anniversary of the death as the 1 year and 10 year dates are important in our traditions. Our lost ones live through us and we remember and celebrate their legacy. These celebrations of life happen not just in Ghana but in New York, New Jersey or London.

Outdoorings

At the other end of the circle of life are outdoorings, the naming ceremony for newborns. These are traditionally held on the morning of the 8th day of life.

The Okyeame pours libation and formally presents the newest member of the family.

The colours are typically blue and white.

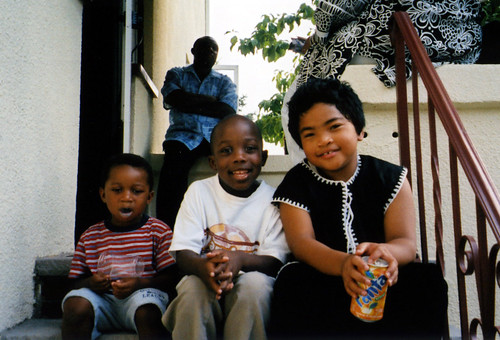

the children look on and learn

The grandmothers are beside themselves. They like to see that things are done properly.

We forget the daily grind of life in the diaspora

and embrace a certain aesthetic of ease on these occasions

Ceremonies qua Ceremonies

Mobile phones are de rigeur these days

The food is always something else, we like to throw a spread...

I normally make a nuisance of myself in the kitchen

It's all about the chairs however...

lots of chairs

We spend lots of time in the heat, under canopies

plastic chairs, sunlight and waiting for tardy drinks

A surprising amount of time is spent simply waiting

Some sights are enough to get you to declaim spontaneous poetry: Kente, Lace and Champagne

There's an art to waiting

For impatient youths, it can be trying: long periods of inactivity

followed by brief spasms of meaning

But as you get older,

you realize it is well worth it.

And almost all our ceremonies end with fun.

We're entertained by the drama in the dance

We hire some drummers

a combo of highlife musicians

(or hip-life djs in recent times)

The Ewes (my maternal tribe) have this propensity to break out into circle dances characterized by everyone pulling out white handkerchiefs.

Boborbor and Agbaza dances happen whether at funerals or weddings.

It is often spontaneous expression.

joyous and playful

We shake a leg - the Gas (on the paternal side) have this propensity for all manner of leg twists and raises.

The maternal side add their Abutia flair

We dance like we come from Tuobodum.

We thank the gods for life.

Even on the streets of New Jersey, even if we don't wear the traditional clothes, we dig in and get down on it.

London too has got soulful expatriates.

Hell, even in Boston, people are known to get down on these happy occasions.

African immigrants have made it to Greenland after all.

In all of these ceremonies I come out of my normally reserved shell to enliven the occasion. I'm known for my village moves back home

I dance with every woman from 3 to 100.

I make people smile at my antics, but, well, I can't help it.

So yes, things may fall apart but these ceremonies keep things together.

Dresses hand sewn by seamtresess with craft and delicacy

We dance in the grand estate and enjoin all in the revelryThese African ceremonies are our relief from immigrant pain

We toast our brethren and sistren with kente, lace and champagne

Index

- African Ceremonies - A slideshow

- African Ceremonies (Better Days Ahead) with Gil Scott-Heron's accompaniment

- African Ceremonies, a playlist.

See also: Scenes from a traditional wedding in Ghana

I nominate this note as part of the Things Fall Apart series under the banners of Social Living and The Comfort Suite

File under: Africa, Ghana, ceremony, photography, essay, perception, culture, festival, wedding, funerals, observation, life, tradition, diaspora, communities, immigration, Social Living, Things Fall Apart, toli

No comments:

Post a Comment