Poetry as Cultural Memory

Kwesi Brew's poem, Ghana's Philosophy of Survival, is a curious beast, one that continues to confound even as it strikes a chord of admiration and indeed recognition. Judging by the title alone, there's no quibbling here about a pursuit of happiness, that laudable aspiration and seminal con. In this reading, the message of Brand Ghana (or maybe even the more general Brand Africa) boils down to survival, and a philosophy at that. You might be a little perplexed and expectant when you turn the page and first encounter the poem. Well, let's not get ahead of ourselves, that's only the title and you can read the rest for yourself. I thought I'd discuss a few poems and consider his notions of cultural memory: the things we choose to remember and to forget. Herewith some therapeutic toli...

He doesn't pull any punches does he? Indeed he comes right out and gets your attention with the assertion that "We are the punch bag of fate". I admire the nerve as well as the craft. You can't help but be implicated in the "we" even if you're not Ghanaian because what follows are stark words. Phrases full of ironic caresses follow from a connoisseur of the school of hard knocks. He has thought long about the topic and is deploying his talents in plain language.Ghana's Philosophy of Survival

We are the punch bag of fate

on whom the hands of destiny wearies

and the show of blows gradually lose

their viciousness on our patience

until they become caresses of admiration

and time that heals all wounds

comes with a balm and without tears,

soothes the bruises on our spirits.

This is the mettle of invisibility.

This is how we outlast and outlive

the powerful and the unwise.

Whether it is best to wait

or engage the scarlet fury of battle

to stay the hand is for the wise to say,

and not the rashness of the moment.

But we have always been here on this land of ours.

Our country is our home and will always be here at home

To watch, listen and take our suffering

'til true happiness comes naturally and without bitterness.

Love of family kith and kin and brother-keeping

has cast us in this mould:

that while we take the blow and seem unhurt,

speechless, we also watch and wait.

Kwesi Brew, from Return of No Return (1995).

He isn't berating a culture of excess, or greed, laziness or similar human failing. He's not complaining, nor is he making any value judgments like the prophets of yore. No. Not quite. There's no moral indictment to be found here. Further, should we go looking in the opposite direction, we also won't find any praise-singing. There is merely clear-eyed reflection on a the workings of a community. We are treated to observations born of the discriminatory sensibility of a curator, observations wrapped with the detail of a wordsmith's weaponry. So, reflection it is. The mood is akin to wist, the atmosphere filled with the cosmopolitan perceptions of the weary.

It's a heavy burden however that he has set for himself. Discoursing on the lack of wisdom of the ruler or the excesses of the powerful is the first order of business. One almost expects this kind of pose of our poets. Still, turning the mirror at a society, as the cultural interpreter is wont to do, risks the weight of unpopularity. You get branded as a shrill gadfly demeaning the national character.

As an aside and recent example, it shouldn't have required much courage to criticize the opportunistic imps that landed us with wars and a depression early on in their misdeeds, but few displayed it. Now that the incompetence of that cabal is the conventional wisdom we all prefer to forget the social hysteria that prevailed and that they were able to exploit, the self-righteousness of the wounded and so forth. Cobwebs, I know, dusty cobwebs...

Returning to the poem, what are the contours of the stated philosophy of survival, I wonder? Let's start with the question of form. This isn't an essay, manifesto or political tract, it is very specifically a poem. The meter is off kilter - read it aloud and you'll see what I mean, I would hazard that this is deliberately so. He is usually very precise in his works. The chosen form is meant to disorient with its mixture of concision and paradox. The skill of the poet lies as much in the choice of words as in what is left unsaid. The tone also is very different from the exuberance of his earlier poems, the ones that excited a generation of Ghanaian writers.

There are certain phrases that are meant to heighten the tension. Consider the journey that starts with "the mettle of invisibility" and ends "the powerful and the unwise". It is worth dwelling on what we pass through: a coping strategy that helps us "outlast and outlive". If there are gems in this philosophy of survival, perhaps it is in a certain sense of community, the social interplay that Kwesi Brew describes as "love of family kith and kin and brother-keeping". Teasing out this clue, we learn that social living is the strategy. It's a protective mesh to be sure, but one that one that liberates from the peril of alienation that invisibility otherwise implies.

I keep returning to the last lines contrasting them with the first. It's an improvement, if not a reversal, with a sense of purpose. Cultural memory is the thesis. We may decide what we chose to remember and forget as individuals, what a society remembers, however, is often in the realm of the historian, who takes her cues from the raw material of the journalist, or the humble bureaucrat whose notes serve to underlie - or give the lie to, the politician or flight lieutenant's self-serving talking point memo. The hope is that a community will harken to the larger and deeper truths of a poet's lyricism, the storytelling of the griots of yore.

If it is sometimes good for a person to forget, it can be fatal for a community to forget. By the same token, it also matters what a community chooses to remember and to forget - the trappings of nostalgia, myth-making and selective amnesia mark out many blind spots in this landscape. The task then for the poet is to speak to cultural memory, to weave the dreams at once and to reflect on the messy muddle from whence we forge our society.

Kwesi Brew was perhaps the most famous of Ghana's poets (he passed away last year) although, and perhaps this is in keeping with his notion of survival, the poet in him was only one of the many lives he lead: diplomat, businessman, politician and so forth. He didn't simply witness the story of Ghana in the twentieth century, he midwifed the country and helped write its story with all its ups and downs, an active voice even when politicians and journalists would decry a "culture of silence". His declared task, and indeed his legacy, was to make sure that we never forget "the voiceless days of the past" as he wrote in another poem - contrast here with "speechless, we also watch and wait". Consider also the threat to "engage the scarlet fury of battle", and the almost Ali-Foreman rope-a-dope strategy he alludes to. Of course there is also is an element of myth making in the stories that we tell ourselves and he made sure to tell his own stories and to influence the things we remember about our small country. The lesson that Kwesi Brew's Ghana has to teach the rest of the world goes well beyond mere survival.

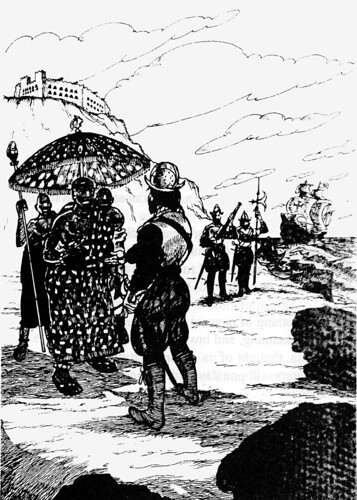

The book of poems in which Ghana's Philosophy of Survival appears, Return of No Return is centered on a trio of long poems imagining the encounter of Africa with the West. The titular poem is written for his good friend and fellow poet, Maya Angelou, "No Return" was his nickname for her and a reference to the Door of No Return that is the feature of Elmina castle and the various other coastal castles on that saw slaves shipped off to the Middle Passage. Sidenote: these days the castles are tourist attractions of a mournful sort, legacy tourism they call it.

There's a story lurking here in the relationship between the two fellow wordsmiths. Maya Angelou, like quite a number of African Americans in the 1960s left the USA for safer and more hospitable climes. Some were in exile escaping J. Edgar Hoover, others the more benign recriminations of the civil rights era, and still others aiming to satisfy that longing for the motherland. In any case Ghanaian literature and arts in general benefited from the encounter - Efua Sutherland, Kofi Awoonor, Ayi Kwei Armah, Kofi Anyidoho and others would be part of Kwesi Brew's milieu.

Sidenote: by the early 1990s African Americans were beginning a second round of engagement with Ghana. The Leon Sullivans and Jesse Jacksons of the black establishment part of the seduction. No return was indeed returning.

Thus the terms of reference are ostensibly about the Return of the Native, and his note to Maya Angelou would deal with that and all the complexities of American and African interactions. He prefaces it however by considering the beginnings of that trans-Atlantic story and the centuries-long engagement with those who would become the colonizer. The two earlier poems in the series bear the title Don Diego at Edina (Elmina) and imagine a couple of meetings between local chiefs and the Portuguese. I think we'll call this poetic license but also much in keeping with Brew's own history. The Fantes were the first to encounter the Portuguese once these latter got their headstart on the high seas. Fantes are stereotypically reputed to be the most assimilated with the West. What stories indeed would they tell themselves about the relationship? His character of Don Diego Azambuja is perhaps based on his poet's notion of the first adventurers. Where does power lie? And how much foresight can we grant? This excerpt is a poet's history:

And the brown in the King's eyes thickened darkly overThe old chiefs were no fools but were confronted with guns, steel and the concomitant "fierce appetites". The second poem in the series, adds The Great Rebuff as its subtitle perhaps indicating the bad turn in this centuries-long conversation. In it the chief's Okyeame (his spokesman) whispers

The presage of gold on hands of iron, gold, gold, gold.

Will there be enough gold to dampen these fierce appetites,

Will there be enough gold, Kyeame?

- from Don Diego at Edina (Elmina)

Remember, Nana, temptation's honour is disgrace.Again, the chief and his advisers have agency and foresight and negotiate as best they can. Perhaps this is an important point in light of the later catastrophe of the slave trade and colonization. He ends the second poem with an observation about nostalgia, moving forward a few centuries and laying the ground for his consideration of the African American yearning for return. He couldn't talk to his soul sister, Maya Angelou, without invoking the African memory of that dislocation and forging a common language. Again the entire suite is all about cultural memory, what we choose to remember and to forget.

The stranger seeks the nether edge of your bed

To snatch your pillow for his head

when sleep overtakes your wakeful care.

Azambuja looked on.

Tell them, Kyeame tell them,

Friends who met but seldom,

Til death parts them.

Savoured the sweetness of untroubled friendship.

The nature of human heart wreaks its mischief

Upon close neighbours each smoldering with his own craving

From unfulfilled desires burst forth consuming anger

- from Don Diego at Edina (Elmina) The Great Rebuff

The collection, Return of No Return, was a departure for Kwesi Brew, less exuberant than The Shadows of Laughter and less expansive than the vision outlined in African Panorama (previously discussed here). A mature meditation and a means to recapture his muse. Always clear-eyed, at times it is a simple critique. Consider:

When in this mood, titles such as Democracy with a Dark Face, Power Perverted should give insight into the focus of his observations. Miracles and the Message is his reflection on the 1983 drought in Ghana another sore episode and one that is rarely addressed, even as its effects linger.The Force Of Evil

When bad men

Pass through a place

The way is closed

Behind them by the injured,

Even to innocent men.

In writing about these topics, he was perhaps responding to a frequent complaint about the short memories of Ghanaians. So when thugs confront us, we should meet them with our active gaze. And just to prove this point here is Kwesi Brew as Jeremiah, inveighing against the military thugs who were then in the midst of their misrule. No one can say that they weren't confronted. Consider this excerpt from A Goodbye to Arms

Where the green khaki struts and grindsThe play on the phrase "free from fear", favoured of election observers everywhere ("free and fair, free from fear") is perhaps the sole levity in that poem, a J'accuse directed at Rawlings and his chameleon crew who were ostensibly shedding their military proclivities (hope springs eternal). The rest of the collection, however, serves to round out the picture with laughter and acute observation. We can all use some laughter to leaven life, some riddles to puzzle over and some landscapes for quiet contemplation and revival. The oral tradition that was our past might have encouraged laughter and forgetting but it was also the font of proverbial wisdom and coping strategies for dealing with tricksters. The poets and writers of our present have their work cut out for them.

its marijuana terror into unarmed hearts,

They come as men-at-arms

badged as justice, grim of face.

And then at last, dissembling cloak removed.

A pack of common traders stained in violence

Wresting bread out the mouths of babies

only to give it back to them at a price

so kind are they who betray us.

Mothers, fathers, children, brothers and sisters

Their own shame stained blood

...

Where is our liberty, you thieves of time?

Where is your vision of prosperity, disciples of greed?

Where is your safety of life, agents of death?

Trusting in these tempers of discontent,

We shall be free again

Free from fear, the fear of fear, the worst

And forever!

A nation's life is a span of just one single bold day!

- from A Goodbye to Arms

There is only one aspect of Ghanaian society that Kwesi Brew's words don't fully address in his works, and that is the growing influence of the new religions. Perhaps the urbane cosmopolitan in him didn't feel the need to consider these articles of faith as he spoke to memory. His message of social living was a worldly one even as it invoked the spirit of brother-keeping. It was simply his duty as observer to hew to that message, to bear witness to an unvarnished Ghana.

He lived then "in a land flooded with ubiquitous miracles" and fought the good fight, fashioning his way in the path of a long line of cultural interpreters. I love the texture of Kwesi Brew's poems, the exuberant efficiency of his wordplay and the complications he teases out as he captures both personal and social moods. His words are a soothing balm when the temptation of wrath beckons, they have the consistency of shea butter, guaranteed to heal open wounds and I feel very close to their vitality.

I often feel impatient about Brand Ghana, the twists in the writing and the frequent setbacks. My elders counsel me that it is best to dwell on the small things, to look at the big picture. Talking the long view is a hard thing for the impatient; watching opportunities pass by as small mindedness prevails seemingly at every turn. After reading Kwesi Brew however, I come back refreshed. I no longer begrudge the sanitized fairy tales that many like to tell about Ghana - they have their uses, and, if anything, sharpen my resolve: resist nostalgia and the larger temptation of myth making. Lyricism and clear-eyed reflection were Kwesi Brew's weapons of choice. We are writing the story, we have been writing it forever.

Poetry A Playlist

- Phoebe Snow - Poetry Man

Deliciously seductive soul music. The Zap Mama remake with Michael Franti is also essential. - Roy Hargrove - Poetry (featuring Q-Tip and Erykah Badu)

Perhaps this belongs more properly on a playlist entitled elation, but I couldn't resist. Like butter... shea butter.

This is the second of some reflections on Ghana, prompted by the recent election. Let's place this note in The Things Fall Apart Series under the banner of social living.

File under: poetry, literature, criticism, review, appreciation, culture, observation, memory, griots, Ghana, Africa, Kwesi Brew, Social Living, Things Fall Apart, toli