My friend Nate pointed out André Gide's Travels in the Congo to me a few months ago. We've been carrying on this occasional conversation about travel writing, perceptions, Africa, Conrad and the like.

In passing he mentioned that the book's typeface reminded him of Rob Giampietro's fascinating article on

the Neuland question which discusses

"Neuland, a "display" typeface hand-carved in 1923 by Rudolf Koch but also Lithos, another "display" typeface digitally created in 1989 by Carol Twombly"...

How did these two typefaces come to signify Africans and African-Americans, regardless of how a designer uses them, and regardless of the purpose for which their creators originally intended them?

Let's have Nadine Gordimer as the token African.

Richard Wright can serve as the token African-American.

There's a discussion about the history of those typefaces and how they came to embody an authentic sense of, well, ethnicity shall we say. "Stereotypography" was how Nate put it. "Blackface" might be another appropriate pun. There's lots to say about such signifiers. I can certainly imagine further papers on "Issues of authenticity and its visual vocabulary: field lessons from Gutenberg's press".

All of which reminded me of the box of

Ubuntu Rooibos tea from South Africa that The Wife had picked up on her travels. It's one of those "sustainable agribusiness", fair trade, touchy-feely things marketed by an offshoot of USAID. The brand names, Ubuntu and Mpuntu, let you know what you're getting into. In case you're not convinced, the obligatory typeface is a great signifier and adds the requisite marketing frisson of authenticity: Africa. Motherland. Earth etc.

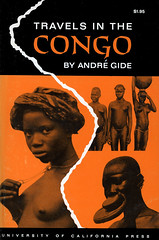

My own copy of the Travels in the Congo arrived in the mail today, and before I could turn the page and note Gide's dedication to Joseph Conrad (all travel writing owes a debt to Conrad so this was unsurprising), I was confronted by the striking cover. I realized that I'd ordered a different edition.

Hmmm. That's more like it. Congo: breasts, nudity, enlarged ornamental lips, pygmies, natives. You don't tend to see these kinds of images on book covers any longer. They'll appear on National Geographic magazines to be sure, or coffee table books, but not on the paperback that you pull out on the bus. It appears that some cultural threshold has been crossed in the recent past, my guess is that this took place around the mid-seventies and there has been a consequent marketing realignment or adjustment.

A more subtle indicator is required and the typeface is one of the few tools product designers have, along with the product names to indicate the essence of the product they are trying to move. You need to know what you're getting but these days we don't discuss race - or at least it's always a very polite discussion. As we say in Ghana: how for do?

A theory formed in my mind that when it came time to revise Gide's work in the later 1994 edition, it was no longer culturally appropriate in the US to display nubile, big-lipped natives, even if they were all the rage back when my 1962 edition was published (that liberal Berkeley Press!). There are probably throngs of academics working on such material.

I amended the topic of the paper to "Changing mores, changing types, changing faces in representations of Africa: field lessons from Gutenberg's press". I like how academic papers seem to go with lots of sub-clauses in their paper titles.

I then remembered that

Fred had discussed

Then I Saw the Congo, a 1920's travel memoir by Grace Flandrau. I put in my order for that book; we all need more writing about Congo.

Its cover is less exotic than Gide's. Its subtle imagery, the silhouetted rowboat of natives on the Congo river dates back to

Stanley's expeditions. The mighty river Congo has great visual appeal and looms large in African iconography.

I turned around, glanced at my bookshelf and immediately noticed a couple of books that fit the visual mold. The first was

In Griot Time, An American guitarist in Mali by Banning Eyre. The ubiquitous font is overlaid on his photo of

Djelimady Tounkara who Teju Cole reckons as the best guitarist in the world - I won't quibble, but what about Prince?

Checking Amazon, I noticed that a

later edition (2002 - only 2 years on) dispenses with our typeface-du-jour and sadly also that the musician, whose face I can no longer make out, is now squashed behind the prison bar-like guitar strings tucked in the cavernous confines of a grey guitar.

What should one make of the demotion of both the black-faced guitarist and our typeface? What was the designer attempting in the reworked cover? In mitigation, one notes that there is the green, yellow and red in the background to indicate the colours of the Malian flag, although one must add, the colours are washed out, perhaps to indicate the ancient status of the music, and of Mali. Authenticity is preserved, I suppose, although the ethnic signifiers have been toned down. I guess it's fair, there was no need to beat the shopper over the head as the original cover did. We could have figured things out from the subtitle.

Robert Klitgaard's Tropical Gangsters also jumped out to me.

It has the great subtitle: "One man's experience with development and decadence in deepest Africa". You don't quite need to write "darkness", "deepest Africa" gets the point across. Now of course

Condi Rice and co. have no qualms dealing with the

Equatorial Gangsters that Klitgaard deconstructs in his book, so I guess decadence is appropriate in the title. Kurtz's moral decay is quite apt when one reads things like the following

hatchet job (Thatcher alert):

Equatorial Guinea had the bad luck to come to independence under Macias Nguema, whose rule was so terrible that a third of the population was either killed or fled. Though he had people garrotted, buried alive and beheaded (and their heads stuck on poles), the detail that sticks in my mind is his having 150 people executed to the tune of 'Those Were the Days, My Friend' played over stadium loudspeakers.

Tropical horrors continue to be our mainstay on the continent it is sad to say. Everyone owes a debt of gratitude to Conrad it seems.

Which reminds me... The best history book on Africa since independence is Paul Nugent's appropriately titled

Africa Since Independence.

If you take a look at the cover, it's as if you are out on a safari, the zebra is quietly crossing the scene in the foreground, the wide trees spread out in vistas of the savanna, you almost expect to spot a lion lazily stepping into to the picture - or an antelope perhaps. Simba. Kimba. Bambi etc. That image has almost nothing to do with the content of this brilliantly-constructed book other than to be a prime stereotype of Africa. Indeed I can't think of an image that could do more violence to the words of this sophisticated book, focused as it is on Africa's post-colonial history and the vagaries of modernity. Is that really the image of Africa since independence?

I'm fairly sure that Nugent had almost no input on his book's cover. Like almost all authors - and certainly all the ones I've pointed out in this note, let alone those South African rooibos farmers - he would have had nothing to do with the packaging of his works. Very few authors have the clout to insist on cover art, they are spent by the time the discussion over the book title is done. Still I almost disregarded his book, judging it as I did by its cover. Perhaps those purchasing history textbooks respond to different things. It goes to show that those cues can have can great influence, whether it is overt imagery or even typefaces.

I amended the paper's title: "Types and Faces: Visual Identites and cross-cultural (mis)understandings - (re)visting the Congo through fonts".

I would normally close with a playlist - and I've had requests for a Heart of Darkness playlist, but that can wait. Instead, apropos the business of not judging a book by its cover, I'll end with a Congolese proverb:

A white tooth has a bloody root.

File under: typeface, design, culture, aesthetic, stereotypes, Africa, black, typography, graphic, history, publishing, USA, African-American, Congo, literature, race, identity, observation, perception, Gide, toli