Voices Inside

Part 4 of the Things Fall Apart series - in which we head to the library...

There is no African writer more loved, or indeed more influential, than Chinua Achebe. Wole Soyinka, Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee were the ones who won the Nobel Prizes (they were all preceded by Naguib Mahfouz of course) and, along with him and a few others, form the canon of the continent's literature (an arbitrary list). Yet, if there is such a thing as conventional wisdom on the African street, Papa Achebe is the people's champion and those others are in the ivory tower. I may admire Soyinka's virtuosity and the sharpness of his intellect (and especially the dramas) but Achebe has my heart. It's not about complexity or even readability - Achebe's narratives are sometimes as layered as the others, it's rather a more direct and emotional affinity with the reader. To apply a musical analogy to the Achebe-Soyinka dichotomy, our man Chinua is Count Basie to Wole's Duke Ellington, the Donny Hathaway to their Stevie Wonder. Or on the comedic front, he's Richard Pryor to Soyinka's Bill Cosby... Well, insert your own heroes if you will, you get the idea: we love them in different ways.

Things Fall Apart remains his most popular novel and has the aura of inevitability that that comes with being the one book about Africa that everyone recommends. There's also the orthodoxy of being assigned reading for many African school children. I tend to prefer A Man of the People or Anthills of the Savannah as I find these later novels more nuanced. Still, like many, I return to Things Fall Apart time and again.

Re-reading it recently, one appreciates the craft with which Achebe constructed his classic tale. It remains one of the most miraculous first novels, a story that possesses great emotional weight. It is specific yet universal, steeped in Igbo traditions but instantly recognizable to all who encounter it. What interests me are the messages that people have taken away from the novel hence I won't rehearse the plot here. The structure though is worth commenting on since it fits the classical heroic frame. There are three parts, in the first, the hero (or anti-hero) depending on your viewpoint is introduced at home and the seeds are sown for conflict, then there is Exile and we end with The Return and the climatic confrontation.

The shocks, as they come, simmer. In the back of your mind you vaguely expected them - the novel after all is called things fall apart. You are greeted in the epigraph with W.B. Yeats' poem, The Second Coming, and the line

Things Fall Apart; The Centre Cannot HoldStill you can't brace yourself enough for them and this is due to the skill of a great writer. You are drawn into the world, almost lulled by the complexities of the traditions depicted. I wonder if it's the descriptions of daily life, the minutiae of rural life, that disarm you. It's much like reading African Cultural Values except it's rendered as virtuoso storytelling rather than a dry philosophy textbook. To be sure, the world depicted is not idyllic, the difficulties are much like Billie Holiday sang, it's not the "pastoral scenes of the gallant South". The shocks are described as a matter of fact but are not dwelled on - perhaps this is why they leave such an impression. As a reader, you want the author to focus on the calamity to help you internalize it. Achebe doesn't give you that satisfaction. True, he will come back to the act later on and will demonstrate its effect - if obliquely, but the point is that life goes on, a rich life force keeps on moving despite everything. The novel is a sly commentary on attitudes and idées fixes about Africa - notions which tend to dwell on the undoubted unraveling that does occur at the expense of the individual stories.

What I had long remembered about Things Fall Apart was the encounter with Europe, the ongoing struggle with the increasingly assertive and proselytizing missionaries backed by a faraway administration. The clash with colonialism and all its trappings: power imbalances, divide-and-conquer, and other tropes. In short, in my memory the novel was a fictionalized counterpart to Adu-Boahen's African Perspectives on Colonialism. This is actually a mistaken impression; that aspect is only a small part of the novel and resonates so memorably only because the novel closes very powerfully - Achebe is a strong finisher. The main thrust and the bulk of the novel is drawing out the African's perspective on things - and what a perspective. Colonialism may weigh heavily but it is treated as a footnote.

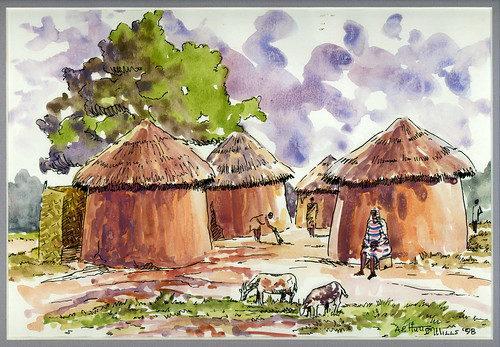

The narrative is about the sometimes bewildering encounters of tradition and modernity. There are details about the way conflicts arise and are resolved between clans and towns, hints about the struggle with the elements, the capricious weather that often leads to food insecurity, the crops that demand perpetual care. The belief system is laid out as is the occasionally faulty biology as exemplified in the way some societies deal with twins. The choice of language is crucial here in highlighting the descriptions. Achebe's authorial voice is simple, deliberate, and slightly stiff, as if passing through a translation phase. The language points to a culture of rich intensity. Things Fall Apart reads like a fable and perhaps this is where the story draws its universal appeal.

A constant risk in writing about Africa is the overuse of metaphor, or casting a wide net. Achebe, like all writers, wrote primarily for himself but also as a reaction to what he read. His first novel is a subversive commentary about metaphorical excess and cultural projections. Paradoxically the novel itself is often seen as a metaphor. The allusive style of writing contributes to the universality of the message. In this way though, it falls in the realm of philosophy something that I think is its only failing.

I will always marvel at the sting of the story's end. The rapidity of the collapse of the proverbial center is accompanied with sardonic asides - note well the satirizing of noblesse oblige. The colonial administrators entirely miss the story and speak at cross purposes. They haven't heard any of the voices that were so ably articulated.

Now of course African literature has moved on in the past half century and even around the time he wrote it, there were many other strands. Others were more playful with language; some dealt with urbanization and the lure of the city. To be sure Achebe is influential but so are many others and African voices continue to emerge. In many African countries there isn't much of an internal audience of readers but good writing does find a way out and one reason is the precedent of the response to Things Fall Apart.

Chinua Achebe's great achievement is to portray a textured Africa - one that is not an undifferentiated mass as seen from the outside. Those villagers in the distance have the same concerns as everyone and are at once mediating modernity and picking and choosing what elements to absorb. He writes from the inside and highlights the ongoing inner dialogues. These days the external forces may be slightly different but they remain mostly unseen: globalization, that thing called the market, or even, dare I say, terrorism. Achebe's response is not to dwell on them but rather to change the perspective. The lesson of Things Fall Apart is to complicate everyone's picture of Africa. Needless to say, I love his brand of complication.

I'll suggest here a musical counterpart to Things Fall Apart: Donny Hathaway's 1970 album Everything is Everything. It too was a quite miraculous debut and influential in its own way. If Hathaway didn't get quite get the pervasive cultural impact of Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, he was in the middle of things, the consummate musician's musician, a wonderful singer and a great and talented composer.

The title song, Voices Inside (Everything is Everything), features one of the most exuberant grooves in the canon. It cuts to the chase, to the essence and the bass. Rendered live in four movements, it ends with one of the most quoted bass solos ever by Willie Weeks. You don't need many lyrics when the music is this strong and infectious. All you need to sing is a minimalist "I Hear Voices / I See People" and let the feeling that you evoke speak for itself.

It is a complete and cohesive album satisfying from beginning to end. Donny Hathaway's artistry is one that emerged fully formed and the proof is that assured manner in which he ends the album - he too knows how to close and the B-side of the album must rank in the pantheon. As a sidenote, I miss the way in which musicians could play with sequencing and moods in the LP format something that has been lost in the move from LP to CD and now to the song-at-a-time present. Consider this four song punch.

First there is direct social commentary in the driving blues of Tryin' Times which covers riots, wars, the "confusion all over the land" and "a whole lot of things that's wrong going down". It's a simple yet poignant lament of "man's inhumanity to man".

Thank You Master (For My Soul) takes you to church a place where a lot of soul music gets its emotional depth. It is memorable not least for the vocal performance but also for the pure gospel celebration of life.

After church, we head back to The Ghetto. Now the ghetto is obviously not a pleasant place, by definition it is where things are falling apart - the school of hard knocks. Still the artistry of the urban griot soundtrack that Donny Hathaway and others produced in the seventies was in humanizing the ghetto's inhabitants and making those voices inside heard. We hear the children crying, the hearty laughter and the disputes. Still instead of being overbearingly dark and scary, you get the sense of an entire world inside. The affirmative twist is in the parenthetical asides, those floating voices. They may sound cacophonous but they are vibrant and as richly textured as any.

The album ends with him making Nina Simone and Irvine Weldon's anthem his own, taking it to church, lacing the song with organ instead of his customary Fender-Rhodes. The title of the song reflects the changing of perspective, the acknowledgment of all of the individualized talent, it is a title that Chinua Achebe would surely nod his head to in approval, the title of course: To Be Young, Gifted And Black.

Next in part 5: Heart of Darkness

File under: Africa, literature, perception, Chinua Achebe, tradition, modernity, culture, Things Fall Apart, griot, music, soul, Donny Hathaway, review, essay, toli

1 comment:

Thank you for a most refreshing look at Achebe.

Apparently it is the book that most often comes to the rescue of people who get stuck at interviews when confronted with:"what was the last book you read?"

How I wish all who claim to have read this book had paid such loving attention to it.

I will now go and read it again, some forty years or so after I read it. Your review will surely help to appreciate the man and the book better

Elizabeth

Post a Comment