The Books of Nima

A note I've been meaning to write for perhaps 6 months to "Sir Sky", the author of The Sea and the Bells; a conversation about Nima, a neighbourhood of the mind.

Part 9 of the Things Fall Apart series, this time an entry under the banner of Social Living...

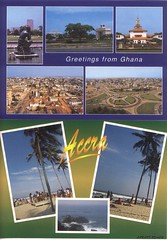

I was looking over your shoulder during your year in Ghana, perusing your travelogue that I came across in a case of web serendipity (the Ghana tag at Technorati, in case you're wondering). When I first read you, and learned that you were going to be staying in Nima, I was apprehensive. Yours would not be the typical volunteer or expat experience; you weren't destined to have the servants, the driver and car, or the air-conditioned office. I don't know if you knew what you were getting yourself into, that you'd be going local and doing the slum housing thing and worse. As an Accra boy, albeit transplanted to Cambridge, I know all about the school of hard knocks called Nima. It looms large in the Ghanaian consciousness, even if there are many worse places these days as you know. It's very far from ideal as an introduction to a visitor.

The fact that you were willing to give of yourself to us was very generous, and I don't know if Ghana fully reciprocated the generosity... The years from 1982 to 1988 broke the back of the Ghanaian people, and ever since, we've been struggling to recover from scarcity and arbitrariness. Thus we demand a lot of outsiders and of anyone who's been abroad. This is changing, and our current quiet stability is restoring our confidence in parts; still, not everyone has read that script, and the neediness can wear you down. For what it's worth, you're not the only one labelled oburoni; my mid-Atlantic self gets that designation every now and then when I'm home.

I was tempted at many stages to jump in: to suggest creature comforts or avenues that would have made things less wrenching for you. But as is the norm on this web, I remained dark matter, absorbing your energy. Still in mitigation of the head nods I omitted to send your way, I think your experience is all the more richer for being yours alone. Like your country's peacekeepers, you are one of Canada's great exports, and after your experience in Ghana, you'll breeze through anything back home.

You lived through countless lights out and experienced the wasted time spent dealing with simple things like water, food and transportation. And of course, there were those untrustworthy and maddeningly inconsistent people... It's the simple fruits of poverty; we lack infrastructure, physical and otherwise.

You had the daily struggle in that library without resources, where you taught the adult literary classes and wrangled to teach those neighbourhood children. The ironies and absurdities about that task are worthy of a novel and hopefully you'll write one.

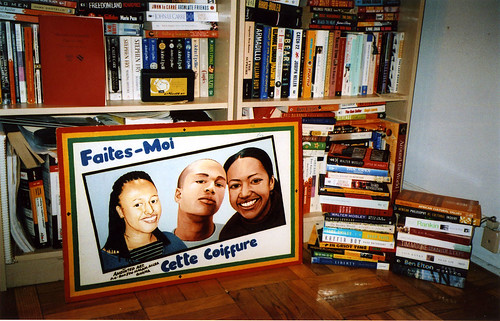

Osu library was the scene of some of my fondest memories of my childhood. It was well stocked and the librarians cared and worried about you. No one could ever tear me away from it, even at closing time. It was where I learned that books and ideas are important, where the parental challenges were investigated and puzzled over. Those books were a long winding road, to be read with care as their nuggets would reveal themselves, or the inconsistencies of an argument would appear in relief in the reading light. My greatest heartache about Ghana today is that very few children are getting the same opportunity. True, our lingua franca these days might be radio, television or this internet thing, but really, how many Ghanaians are participating in this conversational web? If only I could hear those missing voices... The notion that so few in my country can bury their heads in books on weekday afternoons or on a lazy Saturday morning at the library is cause for much distress. And don't get me started about what's happened to the Legon university bookstore. Must everything be utilitarian? Is a country without whimsy worth worrying about?

I think the emotional violence could have been avoided, and, certainly the physical violence should have been avoided. My heart leaped at such times, but still I kept silent and read on. Nima is such an insular place, it is very wary of outsiders as you probably found. In the past it was where rural migrants came to partake of the Accra dream in the Gold Coast. Thus it has always been messy, and developed in fits and starts as befits the residence of those who live on the fringe.

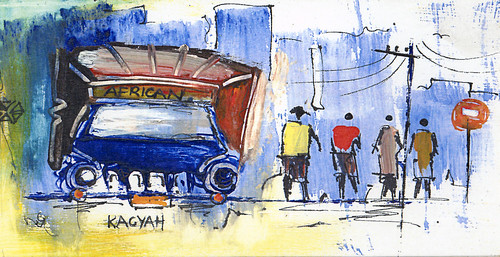

Even today, two shacks away from the homes of proud middle-class schoolteachers you'll find the "Nima boys", selling 'wee', guns or worse, right under the Kanda highway and close to the police station. The boys can always be counted on to roust any political opposition come election time, and their hard knocks usually come for cheap. True, the stereotypes of Nima boys as uncouth, brash, vicious, and ill-educated are extreme, but they carry a kernel of truth about a small minority that lingers even in the relative prosperity of the moment. Across is a chop bar serving the best banku and fetri in town; Auntie Maggie's spot is packed during the day and there's nice fresh tilapia at night, shantytown chic as it were. Just around the corner is a drinking spot with people playing oware or dominoes and downing bottles of Star beer and Guinness in the early evening. Nowadays there are the occasional interruptions when they'll whip out the latest mobile phone ostentatiously: "talking loud and saying nothing".

But you saw all that and more, you saw how people "disciplined children" and how they meddled in each other's business — or not. As you found out, that "it takes a village to raise a child" business isn't happening much in the slums of Nima; too often it is the garden-variety anomie and indifference of urban life, something that wouldn't be out of place in any big city. I saw the same mix in Soweto a decade ago, although that was more upscale at the time, and well, Inman Square is what it is. It is true that given a few decades of development, Nima could become the Catford of Accra, and, believe it or not, it is much better today than it was in the sixties and seventies, but perhaps that progress is cold comfort for the struggles you faced.

I dug your observations on the press and on street life of Accra. Your look at the street cleaning exercises that took place earlier in the year was priceless. In the year 2006, they're finally worried about rubbish and overflowing gutters! And only for two weekends. Ah yes, that culture of maintenance that was so evident in your encounters with us. Perhaps you too have the journalistic impulse. And that water shortage in certain parts of town, Accra is straining at the seams; I was in Ghana at the time and noted as much, although we had water in our neighbourhood. You picked up on our tro-tro wisdom, our folktales, and the languid way in which we view the world. You even taught me that proverb from Northern Ghana:

"Trust God implicitly but always tie your camel up at night."I don't know if that's where Ronald Reagan got his "trust but verify" shtick, but it's close. Still, Kweku Ananse's cunning and laziness can be a curse; living by your wits, hustling in short, is no substitute for the prosaic work of development, although it can be quite enjoyable.

I suspect that a lot of Ghana has rubbed off on you; we can be quite infectious (and not just in matters of public health). Do be careful that you don't break out into pidgin when you're back home interviewing for a job; our deconstruction of the English language has its own musical logic, and not everyone is ready for it.

Take care-oh.And you saw the other side too, the havens of those expats who saw Ghana as a holiday, who kept to themselves and didn't engage with the country and its people. Hell they might as well have been living in Eden; your garden was good old Nima. Well at least you got to know us intimately; that has to count for something. We claim you as our soul sister, and will keep your heart hostage in our town.

You even reported on the beginnings of the cholera outbreak that I encountered last Christmas. When my father began to warn me about taking precautions if I decided to eat out in town, I nodded my head knowingly; for a time you were my favourite Ghanaian newspaper.

And of course there were those malarial episodes, the fevers, the Larium dreams and those hallucinations. How much energy was dissipated in those sweaty nights and days? Those mosquitos, and their cargo of plasmodium falciparum; they are a poverty tax. We may throw our herbal medicine and "bitters" at them, but that is after the fact, to deal with the symptoms. The full panoply of mosquito nets, sprays and lotions counts for nought if you don't deal with sewers and the ever-present pools of stagnant water, or if parents will use their children's nets. And we all know about drug resistance: Darwin's evolution is intelligent design. Still, as they say, mosquitos don't discriminate. Not in Ghana, not on the island of Reunion, and certainly not in Cambridge. We're all singing the West Nile Blues these days. Some call it globalization; I know it as the Mosquito Principle.

You may only have lived in Nima for a while but you got the full Ghanaian experience, unvarnished and cacophonous; three centuries taking place simultaneously in those twisted back alleys. I'll admit to a sense of wistfulness in seeing my country anew through your eyes, and I want to hear more of your thoughts going forward as you carry Ghana in you. I hope we don't weigh too heavily on you. I wish I had been there on the ground; it's hard to be living vicariously through a Canadian woman.

As you'd expect, it's very painful for me as a proud Ghanaian that, almost 50 years after independence, we are still relying, nay depending on you, to teach us how to read, or even to school us about the importance of a book. To read, for God's sake. Hundreds of years after our chiefs started sending their children to Europe to learn these things and we haven't internalized the lessons... But then it works in the other direction, the West relies on people like me to make sense of its world - the technology world in my case. And your southern neighbour, that United States of Anomie, can be a similar school of hard knocks, and not just for lowly immigrants; you don't need to visit New Orleans to get the daily evidence. Still, I wish the cultural interplay was more balanced, that we could each walk tall, rather than smile sheepishly as we do and say, "Only in Ghana" or "That's how it is in Ghana". As if we can't do anything about it. As if it doesn't have to be this way.

You quoted Anthony Hopkins playing C.S. Lewis in Shadowlands:

"Experience is a brutal teacher. But you learn. My God, you learn."I'll suggest in response, our poet Kwesi Brew's book, African Panorama, and I'll quote one of his elegiac poems. You should recognize the subject matter.

The Slums of Nima

Three neighbours met,

And after a hurried, "I give you rest"

The two young men stood aside for the old man

to pass and then picked their way

in the opposite direction towards the alley on the left.

They were thieves who robbed with violence

But still they stood aside for the old man

And he thanked them.

In a bereaved world questions and comments

Fall on unhearing ears.

Only silence, understanding and

Belonging can put

A blind man's stick in the hands

Of a searcher in that night.

The crumbling walls have leaned

On their chests for decades!

The toll of breathing has shredded

Their lungs, and their eyes are sore

With the smoke of the wicker lamps.

And now we all stand at the edge

Of an abyss

Afraid to plunge headlong, or

Return to the dark of the night with them!

Ghanaians are natural storytellers. We are cultural interpreters and urban griots; not for us Anglo-Saxon brevity. Even as we consider Kwesi Brew's abyss, or that heart of darkness, you'll hear the musical laughs and see our urge to understand. We want to change the perspective and open things up through observation and humour. As he wrote in another poem, and I won't give the punchline away, things must be sweet for Ghanaians:

How else could they laughIt is quite poetic that you arranged for your class to travel outside Accra - to the beach no less, and even managed to get them that helicopter ride over the city. We are all so caught up in our black boxes, strangers in our own country. It is eye-opening to glimpse those different perspectives, and you too were being a cultural interpreter, making people see themselves anew. It was a small victory in your ongoing journey.

Like they do when they should weep;

Remembering the voiceless days of the past.

I really hope you don't take your journal down as you threatened recently. The pearls of experience therein are too rich to be simply discarded in the dustbin of the lost web. Allow Google to stumble over your throwaway experiments - they provide comfort even for an audience of one. I dug a lot of the writing (without a doubt, you're on the road to many books). The sound of a voice trying to make sense of an unfamiliar, frustrating yet endearing environment, the large and the small observations, all these things make for a historical document done in best tradition of the web style. The Sea and the Bells, at least that year's version, is a great snapshot of Ghana in the years 2005-2006, a personal introduction to be sure, but it constitutes a compendium of small things to be duly celebrated.

As you might guess, my preferred response to Things Fall Apart is small things: short cuts and bite-sized conversations that engage in the marketplace of ideas. I know you only as "Sir Sky" and the conversation has been one-sided until now. Consider this my opening gambit, my "so what's your name?" approach. I hope you like my brand of small talk; it's known as toli.

Dig: I'm sending some books to the Osu library. I hope it's still there and that someone will receive them. I can only hope that people are still reading. I've been carrying them all these years but never did anything about them; they make a glorious floorscraper. They'll be delivered in your name, and inscribed with the word Nima.

A belated head nod to you.

Next: Dilemmas.

See also: Poetry as Cultural Memory

File under: Ghana, Nima, Accra, Africa, life, experience, urban, slums, conversation, literature, poetry, Kwesi Brew, web, serendipity, observation, culture, interpretation, development, infrastructure, glue, perception, history, Canada, globalization, essay, wist, Social Living, Things Fall Apart, toli